1889 was historically a most eventful year. That year saw the official opening of the world famous Moulin Rouge, a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche. The Moulin Rouge is best known as the birthplace of the modern form of the ‘can-can’ dance. In the same year the Dutch artist, Vincent Van Gough – the famous post-impressionist painter – completed his finest work ‘The Starry Night’, painted during his 12-month stay at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, several months after suffering a breakdown in which he severed a part of his own ear with a razor. It was also the year when New York World reporter Nellie Bly, began her journey to surpass the fictitious journey of Jules Verne’s Phileas Fogg by travelling around the world in less than 80 days. She succeeded, completing the journey in 72 days and six hours.

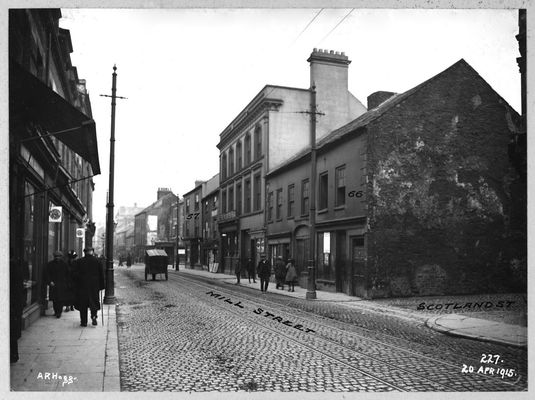

In that same year Belfast saw the unveiling of the ‘bronze sculptured statue of King William III – King Billy – on the rooftop of Clifton Street Orange Hall on 16th November. Established in 1886 it was described by a leading Orangeman as “the finest Orange Hall in Ireland, or it might be in the world, finished and crowned with a magnificent statue…”. At the unveiling a female participant in the crowd was reported as saying of the statue, “The papishes would be cutting their throats when they saw King Billy.”

Such was Orangeism’s contribution to the annals of world heroic endeavour and achievement, cultural, artistic beauty and enlightenment in 1889.

The Londonderry Sentinel of 19th November, reported the occasion was treated in Belfast as akin to a general holiday by enormous numbers of people. An estimated 50,000 Orangemen reportedly arrived from various places in Belfast and across provincial Ulster, special trains having been laid on and countless processions arranged to descend upon Carlisle Circus and Clifton Street areas for the ‘magnificent occasion’ with approximately 112 Orange districts represented.

The contract for the manufacture of the statue was placed with Mr Harry Hems of Exeter, an eminent sculpture; another company was responsible for casting of the statue… “which is a work of art in every sense of the term. It represents the great champion of civil and religious liberty, on horseback, with uplifted sword, his face being turned to the rear, as if in the act of encouraging his followers to advance the conflict.”

The statue cost £600, was 12 feet to the upper lifted hand and 15 feet to the point of the upward lifted sword. It was 37 cwt in weight. The stirrups, saddle cloth and pistol holsters have been taken from castings of the originals and the sword was a copy of the King William wielded at the Battle of the Boyne. The uniform was copied from the costumes then preserved in the Tower of London – “therefore, artistically and historically, the statue is complete in every respect.”

The Northern Whig reporters after privately viewing it on November 5th, said simply, “It is in every way an excellent work of art, and will prove a handsome adornment to the Clifton Street Orange Hall.”

Background

On November 9th, the Belfast Weekly News detailed the context and background to the Cliton Street Orange Hall ceremony and unveiling of the statue. Countless celebrations of various sorts were held on the 5th November particularly across provincial Ulster, and elsewhere in Ireland, including Dublin, and Orange networks in England and Scotland to mark the bicentennial commemoration of Prince William’s landing in England on that date in 1688. Secondly, other commemorative events for ‘loyal Protestants and Orangeism to mark the anniversary of the ‘Gunpowder Plot’, when Guy Fawkes and his fellow “Popish conspirators” plot to, “…to massacre and blow up the Protestant House of Parliament with the Protestants it contained” was thwarted by the, “…interposition of Almighty God”, who stopped 36 barrels of gunpowder from being ignited in the cellars underneath the Houses of Parliament in London. Finally, there were celebrations marking the defeat of the Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill for Ireland in 1886, averting “civil war” in Ireland.

Other local ceremonies, parades, and lectures took place and special occasions to mark the formal opening of newly erected Orange Halls in Killycoogan near Ballymena, Lisnadill Orange Hall near Armagh and even in England on the quay of the fishing own at Brixham, Devonshire, where a life-size marble statue of King William was unveiled near the spot where William of Orange landed on 5th November 1688, later William III of England.

Unveiling of Statue of King Billy

The procession of 50,000 Orangemen was a large and imposing one. Many dignitaries were present with various titles, including: His Grace, Grand Master, Duke, Earl, Captain, Major, Colonel, Admiral, Sir; many others were listed as ‘JP’, Justices of the Peace, and several were Unionist MPs – Colonel Saunderson and William Johnson. The ceremony for unveiling took place from the drawing room of leading Orangeman Brother Lilburn, editor of the Belfast Newsletter, whose residence at 11 Clifton Street was opposite the Orange Hall. The speeches predictably focused heavily on Orangeism’s incomprehensible concept of ‘civil and religious liberties’ achieved at the Boyne for the Protestant inhabitants of ‘Ireland and Europe’. In reality this meant for Ireland, contempt, domination and control of one’s ‘Papist’ neighbours and a psychotic hatred of the head of the Catholic Church, the Pope, believed to be the ‘anti-Christ; an equal level of fear of the political power and advance of Irish nationalism; and annually wishing one’s Catholic neighbours in hell during every terrifying 12th July celebration by the Orange Order which was established 1795.

Br Thomas McCormick, Grand Secretary, addressing Mrs Saunderson, wife of Colonel Saunderson, Conservative and Unionist MP for Belfast, said: “Madam I have pleasure in requesting you to unveil the bi-centenary statue of William Prince of Orange and King of England, raised by the Orangemen of Belfast to perpetuate the memory of a prince of rare virtue, courage, fortitude, and sagacity, who under the blessing of Providence, contributed largely to advancement of the civil and religious liberty of England and the whole world.” Mrs Saunderson then unveiled the statue amid the cheering of thousands.

Ceremonial Speeches

The Rev. Dr Kane, Grand Master of the Orange Order in Belfast, then delivered the oration that strongly alluded to their apparent sheer terror of the Irish nationalist Home Rule movement’s agitation for a devolved domestic Parliament in Dublin for Ireland.

“We dedicate this statue to liberty, and to the cause to which liberty in this country is inseparable – the cause of the legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland. And… the first vow we register before that unveiled statue, with the memories of heroic sufferings and deeds crowding our minds—sufferings and deeds which point out the path of duty to successive generations of loyal Irishmen—is that we shall never trust our lives and liberties to the care of a Parliament conceived and composed of men who are steeped to the lips in treason and crime. We reiterate today, solemnly and deliberately, that there is a limit with respect to us which even the three estates of the realm have not the authority to overstep. And if by any extraordinary misconception of the contract between us and them they should overstep that limit, we vow that we shall never recognise any Act passed by them in excess of their powers over us…and disowned by the parliament under the jurisdiction of which we were born, we shall claim the right who our future masters shall be, and what shall be the conditions of our future national existence.”

And he continued: “…The most illustrious soldier of the present day is an Irish loyalist…I do know that there are ‘600,000’ Orangemen in the British dominions who can be confidently counted upon by their brethren in this country; and I further know that in every arm of her Majesty’s service, both by sea and land, there are men who in the ‘mystic bonds’ of the Orange Institution are pledged to maintain the Protestant religion and the constitutional liberties of the people of these realms….Here, then, today inaugurating the bi-centenary statue of the immortal hero of civil and religious liberty, we vow in the face of mankind and in the face of high heaven that we shall never surrender to any political arrangement which would destroy or even circumscribe our civil and religious liberties.”

Colonel Saunderson, Conservative and Unionist South Belfast MP, and another staunch Orangeman, described the scene.

“…Belfast and Ulster assembled in their thousands for the one great object of commemorating the memory of a man who is dead, but whose spirit lives in the country he saved from ruin and in the people, he saved from slavery…We commemorate the memory of King William III. He fought the same foe that confronts you and confronts me…and has for its object and aim the same ultimate intentions. Their methods are murder, treason, intimidation, and robbery, and the end and aim at which they aimed then, and at which they aim now, is this—the disruption of the empire and the subjugation of every Protestant, every freeman to the dominion of Rome. Against that King William fought; against that we are ready to fight.”

After the unveiling William Johnson MP, identifying himself as, “the Orange representative of South Belfast in the Imperial Parliament”, spoke of the necessity of… “keeping the rifle in one hand and the Bible in the other while the liberties of Protestantism were threatened.”

'Abysmal and unacceptable' 2022 Twelfth could lead to Belfast's Orange parade changes https://t.co/tanQHs8gGi via @ATownNews

— Andersonstown News (@ATownNews) July 7, 2023

On Monday 18th the Belfast Newsletter wrote approvingly, that at long last the matter of a statue to memorialise King Billy was finally erected, given that Belfast was the ‘capital of Ulster and the strong-hold of Protestantism and Orangeism’. The Northern Whig on the same day provided a full report on the speeches of the Orange Order – their proclaiming of the need to prepare Ulster as a bulwark against the Irish nationalist movement, and as Belfast had gained city status lately (1888) that the King Billy statue should be the influence and inspiration for defining Belfast and Ulster loyalism with many more public statues and symbols erected in the city to define its ‘Protestantism, Orangeism and Britishness.’

At a post celebration event a leading Orangeman said that, as they regarded Belfast as the ‘metropolis of Orangeism’, it was a pity a similar statue had not already been erected on a grand pedestal in Castle Place in Belfast. This was the Orange Order’s concept of ‘civil and religious liberties i.e., to use statues, street names and Orange parades to bully, taunt and humiliate and impose their will, domination and control over Belfast’s nationalist and Catholic citizens.

On the 23rd of November the Belfast Weekly News offered an alternative perspective of the event.

“Considerable curiosity existed as to the strength and stamina of Ulster Orangeism, and several years having elapsed since it last gave the citizens of the Northern Athens an opportunity of judging its all-round progress. Crowds assembled along the line of the route to see and judge for themselves. Catholic and Protestant evinced an equal desire to witness the procession, and though most of them treated the business with supercilious contempt on the score of demonstrative recognition, the day’s programme possessed a fascination for those who were disposed to indulge an idle curiosity touching it.

“The statue apart from its merits as a work of art… is scarcely deserving of all the praise bestowed upon it. If placed within easy reach of those for whose edification it is intended it would look magnificent enough, perhaps; but the effect, as it stands at present, is ludicrous in the extreme, and, brethren were heard expressing an opinion in that burden as the crowd began to separate…”

The newspaper added: “A ceremonial dinner was held at Mr Lilburn’s home opposite the Orange Hall…A galaxy of Ulster nobility were invited. Colonel Waring’s communication of apology (for non-attendance) was singularly appropriate. It told the company that he was “knocked up” and could not honour them. At the close of the day’s outing Orangeism as a whole looked as if it too were “knocked up,” and so it retired, and the city resumed its normal appearance.”

Conclusion

The unveiling ceremony of the stature of King Billy in November 1889 was highly orchestrated and planned. Given its positioning on the Orange Hall’s ‘high rooftop’, the sheer scale of the event with a reported 50,000 Orangemen and supporters present seemed incompatible with one another. The real significance of this event was as a show of strength by Ulster Orangeism/Unionism and a political statement of its unequivocal opposition and resistance to the Irish Home Rule Movement and strengthen the cohesion and discipline of the Orange Order as a religious, cultural and potentially militant movement for Ulster unionism as stated in their speeches.

This Ulster Protestant provincialism, particular within the north-east, had history, politics, culture and religion at its heart and was characterized by a sense of Britishness, Irishness and ‘Otherness’. ‘Otherness’ was reflected in the peculiar characteristics of the Ulster Protestants of Anglo/Scottish stock, which set them apart in provincial Ulster, from the other three provinces of Ireland but also from Britain given their ancestry as being a largely settled colonialist society planted in Ulster after the series of plantations in the 17th century directed by British royalty and military powers, and underpinned by both their dependency on – but also their distrust of – the British political establishment. This phenomenon of multiple identities and the later 20th century unionist/loyalist expressions such as is still used by unionists/loyalists to describe the north-eastern part of provincial Ulster as 'Our Wee Country', has potentially some similarities to what is classified in psychological terminology as ‘Dissociative Identity Disorder’ (DID), and was best articulated by the Belfast Irish News in 1907.

“Belfast is a city which suffers from unsatisfied aspirations and baffled aims. Her imagination is starved and she is oppressed by an intolerably grey monotony. She is the loneliest city in the world. She would be happy if she were on the Clyde, for her blood is Scottish. But she lives in exile amid an alien race. She has ceased to be Scottish, and she is too proud to be Irish. She has the hunger of romance in her heart, for she has lost her own past, and she is groping blindly after her own future. She cannot identify herself with Ireland, or with Scotland or with England and she vehemently endeavours to give herself to each country in turn. She is like a woman who dallies with three lovers and cannot make up her mind to marry any of them.”

Brendan Muldoon©2023