Part 2 1860 -1913

THE Belfast Commercial Chronicle (1845), proudly wrote of the Belfast District Lunatic Asylum, “The harshness and cruelty of the old mode of treatment are, in this valuable institution, entirely done away with; and the freedom from personal restraint enjoyed by the patients so far from being an evil, has been attended by the most beneficial results.”

Its success was accounted for by the visionary work of its managing superintendent, Dr Robert Stewart who applied humane ‘moral treatment’ therapies, adopted in all newly established Irish District Asylums following the 1821 Lunacy Act (Ireland). The importance to all asylum ‘inmates’ of the ‘patriarchal presence’ of Dr Stewart was described by the Belfast Commercial Chronicle (1847), “To calm the mind, and mellow the agitated, and rough passions of his charge, is illustrated daily by Dr Stewart, in his assembly of motley characters, who love him as a parent, and catch cheerfulness from his smiles.”

How far were these claims for the Belfast asylum true and realistic? Moral treatment 'offered a humane’ environment for promoting ‘care’ and ‘recovery’ of the ‘insane’. The evidence indicated in the 19th century that treatment of insanity focused on ‘control’ of long-term insane inmates, inducing the profound dilemma of ‘institutionalisation’ for 85 per cent of the patient population at all 22 Irish district asylums. The main obstacle was the limitations of knowledge of the causes or potential cures for mental ill-health by psychiatry and the focus on compassionate environments and positive staff/patient relationships, rather than scientific/medical treatment of mentally ill patients.

Moral Treatment and Institutionalisation

These problematic issues were unwittingly revealed often by newspaper reporters who mistakenly assessed the success of the Belfast Asylum based on superficial observations of patient’s behaviours and physical environments, rather than questioning the nature of applied medical practice and curative therapies for mental ill-health, if they existed at all. On Monday 17th March,1862 the Northern Whig reported on several visits by inmates of Belfast District Asylum to Bells Hippodrome circus.

“In every respect, the deportment and bearing of this interesting portion of the visitors to the circus were ‘scrupulously correct’. The ‘delighted countenances and well-timed cheers’ at the varied and wonderful feats they beheld, could not but have gratified the philanthropist, and all who are well-wishers of this ‘humanising treatment’ of this fellow man when prostrated under the effects of mental aberration.”

This interpretation of the ‘success’ of ‘moral treatment’ where ‘lunatics’ merely appeared ‘conditioned’ or ‘tamed’ to behave like well-trained obedient pets underlined the failure of implementing medical ‘curative approaches to mental illness'. The emphasis was on behaviour modification and conformity rather than on medical practice aimed at curative approaches for their condition. The commentary hardly suggested free thinking individuals improving through personalised mental health care programmes aimed at recovery and cure.

Dr Stewart later observed, “…the inmates generally enjoying music, and many of them who are totally inert and immovable on ordinary occasions, becoming lively and active when the sound of music is heard, and, more especially, when conjoined with dancing, an ‘amusement’ in which they are allowed frequently to indulge themselves.”

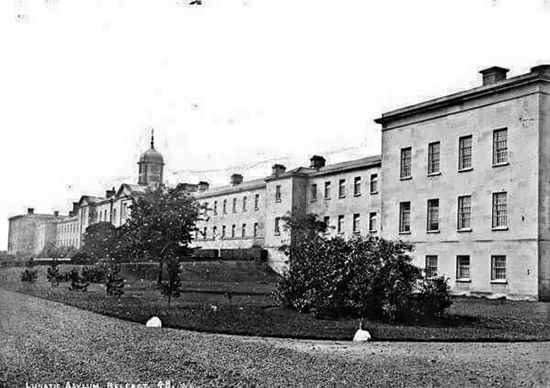

The Belfast Asylum where the RVH now stands

This observation was telling for how music and dance were used for leisure and for mood elevation, and as another method of ‘controlling behaviour’, in place of applied medical interventions and curative therapies. The focus on presenting annual ‘dance and musical extravaganzas by the asylum ‘inmates for invited dignitaries and press, as a measure for judging the success of the asylum’s patient’s treatment was not insignificant. In the Belfast Asylum up to 150 patients were supervised for disciplined orderly walks to such as Botanic Gardens, accompanied by their own brass band. One commentator said, “Institutional demonstrations of this style showed the outside world that the asylum had restored order, decorum and obedience in those who were previously uncontrollable.”

Dr Stewart’s observation conjures up images of the associations of music and revelry with insanity through classic Hollywood horror films, such as when Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's Monster is ‘overjoyed’ when he hears music for the first time, played on violin by the blind man in ‘The Bride of Frankenstein’, (1935), or ‘Bedlam’ the 1946 American horror film starring Boris Karloff, based on the notorious 18th century lunatic asylum in London, when its vicious, and cruel Master George Sims (Boris Karloff) appeases Lord Mortimer, a patron of the asylum, by having his "loonies" put on a musical extravaganza to convince him of the success of the asylum’s ‘care’ and humane treatment of their inmates.

Suicides and Murder

Then there was the darker side of asylum life: suicides. During the 19th century between one-quarter and one-third of all patients admitted to a lunatic asylum in Britain and Ireland were described as ‘suicidal’ on their admission papers. In the Belfast asylum there were dreadful cases of patient suicides by hanging themselves in their cells with bedsheets or cutting their throats or poisoning. If concerns existed of intention of self-harm, besides close supervision, strait jackets could be applied and used exceptionally into the 20th century.

The image of idyllic humane social environments in asylums belied the reality of violence between attendants and inmates and high-profile cases of patients murdering other patients including at Belfast.

In Belfast an inmate named William J Dickson murdered two inmates on 6th May 1911 in the asylum’s gardens using a hatchet. The inmates were engaged in gardening work in the asylum grounds. Dickson without prior warning suddenly went berserk killing two patients. On patient was struck repeatedly on the head as he lay sleeping on a garden bench – James Elliot an inmate of 15 years aged 34 – a “harmless, cheery and kindly” patient. Two other inmates, Samuel Verner aged 31, and John Sheeran were seriously injured; Verner died later of head injuries. Dickson was described as generally a “quiet decent man” by the attendant at the coroner’s inquest, stating, “he was the last man I would have suspected of causing trouble.” He was subsequently found guilty of homicide on the grounds of a ‘homicidal impulse’ and not ‘murder’ at the coroner’s inquest.

In another case at the Belfast asylum, William Smith confessed to murdering another inmate Thomas Fearon, aged 24, in his ward by strangulation, after his body was found on the floor of the room with a cord tied round his neck. Smith shared the room with Fearon and another patient called Nelson, who was apparently asleep at the time of the killing and unaware that it had happened. Smith tried to escape by jumping 20 feet from a window but was apprehended. He later confessed and was found guilty of ‘wilful murder’, and sent to prison (Belfast Morning News,1863).

The general impact on ‘recovery, and cure’ from the condition of insanity was increasingly questioned and the ‘accepted causes’, and treatment of insanity re-evaluated. Were assigned causes of ‘insanity’ merely symptoms of other illness?

For example, the 23rd annual report (1853) of the Belfast District lunatic Asylum notably reported that the main single cause for that year’s new admissions was ‘intemperance’ (chronic alcohol abuse) – 12 per cent of total cases. This was classified as one of the main causes of ‘insanity’ with admissions and re-admissions. Dr Stewart suggested that the Lunatic Asylums for the insane were not appropriate for chronic alcohol abusers but alternatives provision such as a “Reformatory for Drunkards”, where they could be treated for their alcohol abuse, as intemperance is a “disease and requires skilful and delicate treatment.”

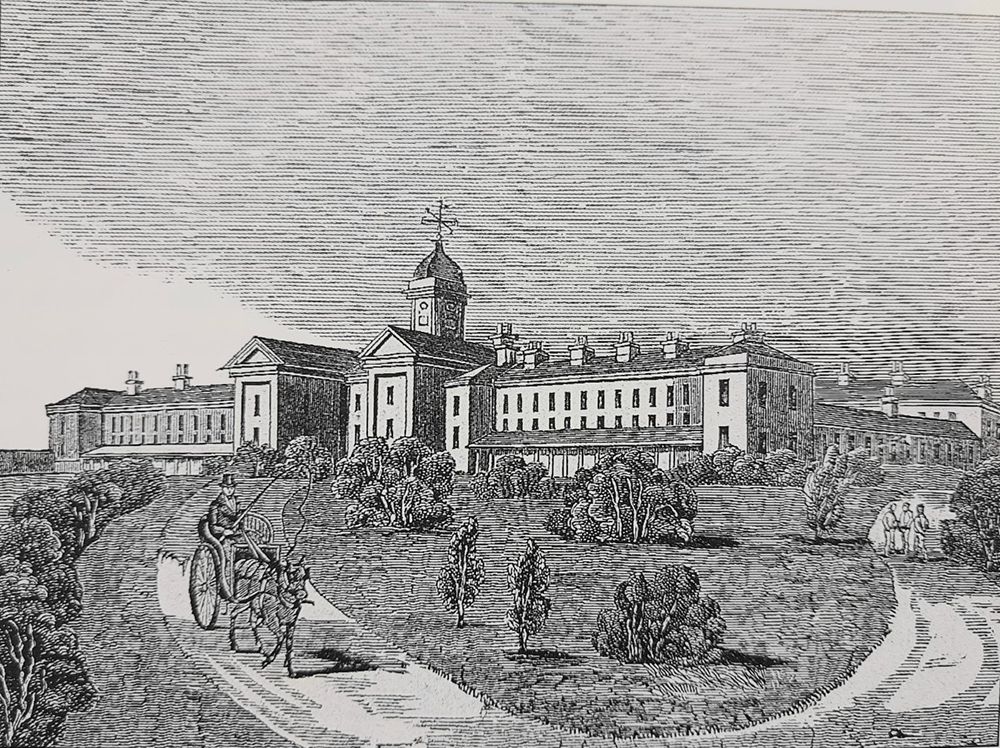

Engraving of 1829 of Belfast District Lunatic Asylum on its completion

From 1840 a cause of insanity and committal to the Belfast and other asylums included ‘epileptic’. There may have been cases of ‘insane and epileptic’ but limited knowledge of its causes and the dangers of seizures led many to see asylums as safe and secure places ‘irrespective of an epileptic patient’s ‘mental state.’ During the 19th century the asylum inmates with epilepsy normally remained as long-term patients and died there of what was believed to be an incurable affliction. Likewise, inmates whose insanity was ascribed to ‘paralyses’ normally referred to inmates with neurological degenerative illness caused by ‘end stage syphilis’ and ultimately fatal at the asylum – ‘syphilitic insanity’.

Treatments were modified or newly introduced towards the last quarter of the 19th and early 20th century. Besides moral treatment’s humane approach to patient care at the Belfast asylum, hydro therapy was also used, as cold baths and showers were believed to help relieve mania and hyper excitability. Mood altering drugs and medicines were introduced from the 1860s and increasingly thereafter, often ‘experimental’ in nature with patients without sufficient clinical trials. Drugs were mainly used as sedatives, hypnotics or anticonvulsants, including potassium bromide, chloral hydrate, chloroform, sulphonal, opium, morphine and many others, used as much for ‘chemical restraint’ i.e., ‘controlling’ by drugging patients’ as for any medical curative outcomes for mental illness. Their use became controversial given the dangerous side effects and there were reported cases of patients deaths occurring as an outcome of their use in asylums. Sulphonal was found after years of use to accumulate in the kidneys, causing poisoning and often death after continual use.

Cure rates and Recovery

The effectiveness of asylums on recovery rates for patients became highly controversial. With patients under treatment those designated ‘cured’ was about 11 per cent and ‘improved’ about four per cent; typical outcomes rates for asylum patients in the second half of the 19th century. The figures for the Belfast Asylum summed up the awful reality for so-called cure and improved rates for insane inmates. Dr Stewart stated in the tenth annual report of the Belfast Asylum (1840), that the asylums were set up according to the 1821 Lunacy Act, to provide support and care for the distressed lunatic poor for ‘temporary periods’ to help “soothe the diseased mind” of medically ill people within a supportive location.

The figures for the duration of residence of patients at the Belfast Asylum reported in the 35th Annual Report (1865), were a shocking revelation, if ‘temporary’ was the intention. Out of 362 patients remaining under treatment at 31st March 1865, there were 28 patients in care from 1-9 months; 116 from 2-6 years; 66 from 6-10 years; 38 from 10-15 years; 59 from 15 -30 years; and nine from 30 years plus. Many patients committed to the asylum lived and died there and for long term patients the lunatic asylum was not a place for any hope of cure; describing lunatic asylums as ‘curative environments’ was plainly absurd. They simply became a more comfortable and preferred existence to the awful lives of poverty and hardship, patients left behind.

This highly significant conclusion was clearly accepted in the 15th Report of the District and other Lunatic Asylums in Ireland (1866) identifying precisely the challenges, “…that the accommodation provided in district asylums…should not only be sufficient in extent, but that those institutions should have, as much as possible, the character of hospitals for the ‘curative treatment of the insane’, rather than of simple receptacles for their very safe keeping.”

Overcrowding

The next major challenge facing Irish asylums in the later 19th century was severe overcrowding. After the Great Famine, Ireland’s population, was vastly reduced by 20 per cent in 1850; a loss of two million people. A steady decline continued for the rest of the century, largely due to emigration, and yet the numbers in Ireland’s asylums in all age groups with male and female admissions rates consistently increased in the decades up to 1914. The growth in total patient numbers in Ireland’s district asylums was staggering. In 1851 there was 3,234 patients; by 1901 there were 17,000, and by 1913 almost 25,000 patients “crowded promiscuously together without order or regularity into a human mass of mental degradation and confusion.”

A Victorian restraint jacket

Of severe overcrowding at the Belfast Asylum the 42nd Report of the Inspector of Lunatics in Ireland, (1893) stated, “…it is quite impossible to go through the Belfast Asylum without being struck with the evils which attend to overcrowding in such an institution. Through its baneful influence the efforts of the staff are dwarfed and cramped so that it becomes impossible to devote the necessary time to the treatment of individual cases. The excitable are rendered more violent, the melancholic more depressed, and the many otherwise quiet patients are rendered discontented and irritable.”

“…visit the so-called refractory divisions (say No 6 female), on a wet day when the 87 patients who occupy it are confined to their rooms, where they will witness the evil effects of crowding a number of excitable, or indeed any patients into rooms without proper outlook or surroundings, a scene of anger, turmoil, foul language, and course laughter, which will quickly drive them away saddened and horrified…”

The challenges were clear – Belfast Asylum accommodated 104 patients in 1829, but by 1865 it increased to 362. By 1900 there were 685 patients with several hundred more placed in outreach locations, such as the Belfast and Ballymena Workhouses. The success of ‘Moral Treatment’ based on ‘manageable numbers’ had catastrophically failed.

By the early 1900s the urgency was to arrange new accommodation, designed entirely differently from the one building model of the old Belfast Asylum on the Falls Road – a series of ‘villas’ for 50 or so patients in each at the new Purdysburn site.

Dr Graham’s the asylum’s Director published his report on ‘villas and asylum reorganisation’ (January 15th 1901). “The personal care and watchfulness of the attendants in charge of various villas would be a living safeguard of more value than the mechanical watchfulness of attendants accustomed to depend mainly on locks and keys”.

The villa style model would offer more homeliness, less institutional in character and much preferable to large crowds living under one roof. “The idea of a home is, in fact, at the bottom of the villa colony system.” The Belfast Asylum closed and relocated entirely to the new site of Purdysburn Villas in 1913.

Conclusion

The scientific inquiry of the causes of insanity by psychiatry was limited by the end of the 19th century. What so-called ‘moral treatment’ provided in practice was orderliness, discipline and routine but ‘not cure’ and the profound reality was that most patients were simply ‘institutionalised.’ By 1900 medical practice in asylums was far behind advances in other branches of medicine and largely irrelevant for the majority of asylum inmates. The ‘The Banner of Ulster’ (1849), described ‘lunacy’ as the “wrecked and tottering elements of dismantled and disordered nature.”

Perhaps a more insightful view of insanity was provided by Edgar Allen Poe who wrote,

“Men have called me mad; but the question is not yet settled, whether madness is or is not the loftiest intelligence – whether much that is glorious – whether all that is profound – does not spring from disease of thought – from moods of mind exalted at the expense of the general intellect.”

Brendan Muldoon©2023