Martin McGuinness biography an engrossing read

A COFFEE-table book, I suppose you’d call this. I’ve a few coffee-table books in my house and while they’re nice to look at and add a House and Home touch of style to the living room, they’re not what you would call insightful. Or revealing. Or personal.

With ‘Our Martin’, Jim McVeigh has pulled off the not inconsiderable feat of combining the desirability of a glossy and attractive coffee-table book with an insightful, revealing and personal biography of his friend and comrade Martin McGuinness.

The format of the book – large; high production values; photograph-rich – means that it’s a relatively short and compact telling of the McGuinness story that could easily be devoured in one sitting (I did it in two). But it’s beautifully and engagingly written by author McVeigh who’s now four books into his burgeoning literary career and displaying an increasingly deft storytelling touch.

His story of Martin McGuinness’s life is rolled out in traditionally linear form, consisting of seven chapters, kicking off with his boyhood in Derry, meandering entertainingly and informatively through the civil rights and Troubles years; his first meeting with Bernie, the love of his life; the peace process; his love of family; his passion for literature and the outdoors; and his passing and legacy.

CHUCKLE BROTHERS: Martin McGuinness struck up a surprisingly cordial peace process relationship with Ian Paisley

The early Bogside years I found particularly engrossing, perhaps because I knew and know – like most people – a hell of a lot about McGuinness the IRA volunteer and senior politician, but not so much about his time and his place in the city that produced and shaped him. His family background, his school years, his love of a wide variety of sports (but not yet cricket) unfold before us accompanied by a judicious and evocative selection of photographs, old and not so old.

The chapter on his politicisation and militarisation by the increasingly flagrant depredations of the Stormont regime and the civil rights reaction will of course be of huge interest to readers of the book, who will no doubt be delighted to fall on a number of fascinating, previously unpublished pictures of McGuinness’s days as a young IRA volunteer in Derry.

But it is in the relating of the gruelling, dispiriting, hopeful and inspirational peace process that McVeigh’s writing comes into its own. He’s no detached and interested bystander, as are most biographers – he’s someone who was at the heart of Sinn Féin during those historic years. And while that has the potential of allowing the narration to slide into partiality or even hagiography, McVeigh manages adroitly to avoid both, laying out instead an engaged and knowledgeable timetable of events that, while limited in length and scope by the book’s modest wordcount, is satisfyingly comprehensive and revelatory within its own strictures.

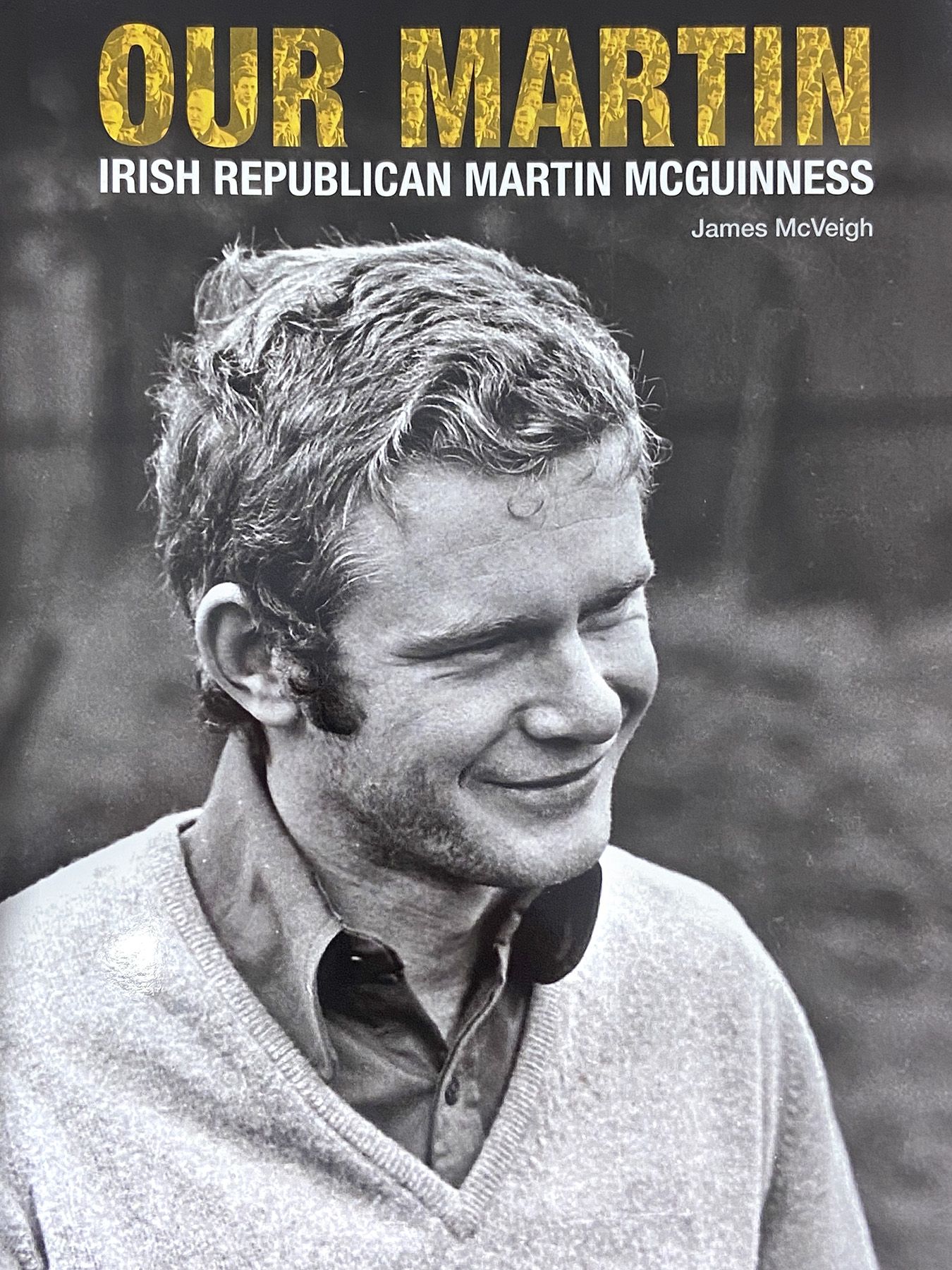

MAN OF WAR, MAN OF PEACE: Jim McVeigh's new book deals with all aspects of Martin McGuinness's eventful life

Perhaps Martin McGuinness’s greatest strength lay outside the twin fields of resistance and politics to which he devoted the greater part of his life. It was a gentleness and a personal affability that were so deeply and naturally ingrained in his personality that it drew people to him – and to what he had to say. The extent to which these qualities enabled bumps in the road to peace to be overcome will never be known – but we can be sure that it was hugely significant.

Two particular things stand out for me in this regard. I first met Martin McGuinness in Sevastopol Street in the mid-80s, when the terraced homes all around the Sinn Féin offices were being pulled down. We were standing at a window as we spoke and he frequently broke off to watch the bulldozers bring a century and more of history crashing down in plumes of brick dust. He welcomed the redevelopment, but he wondered aloud what lives had been lived in those homes, what stories lay under the piles of debris; and then he said to me, stretching those long Derry vowels even longer: “You know, it’s very sad in many ways.” And in his face as he watched the scene across the Falls Road, I could see how much he meant it.

At the Aisling Awards when Martin was guest of honour, I was seated beside a unionist politician and his wife when McGuinness – then Education Minister, I think – arrived amidst a phalanx of selfie-seekers. The politician’s chat seemed a little awkward all of a sudden and he travelled verbally around the houses a bit before finally reaching his destination: “Do you think we could get moved over beside him?” he asked me. “He seems really nice,” the man’s wife chipped in.

I can’t remember if I managed to change the seating arrangements, but I do remember thinking at the time that if there was a political quality more important than sheer likeability I didn’t know what it was.

Perhaps McGuinness’s broad and wide non-public hinterland – his spirituality, his poetry, his painting, his people personness – added extra layers to his personality that drew people in. There’s certainly plenty of evidence here to back up that contention.

Be warned, though. Having bought the book you’ll be faced with a bit of a dilemma: Do I keep it on the coffee table for others to admire, or do I put on the bookshelf?

Our Martin

By James McVeigh

Published by Beyond the Pale

Available in bookshops or online at beyondthepalebooks.com

£24.99