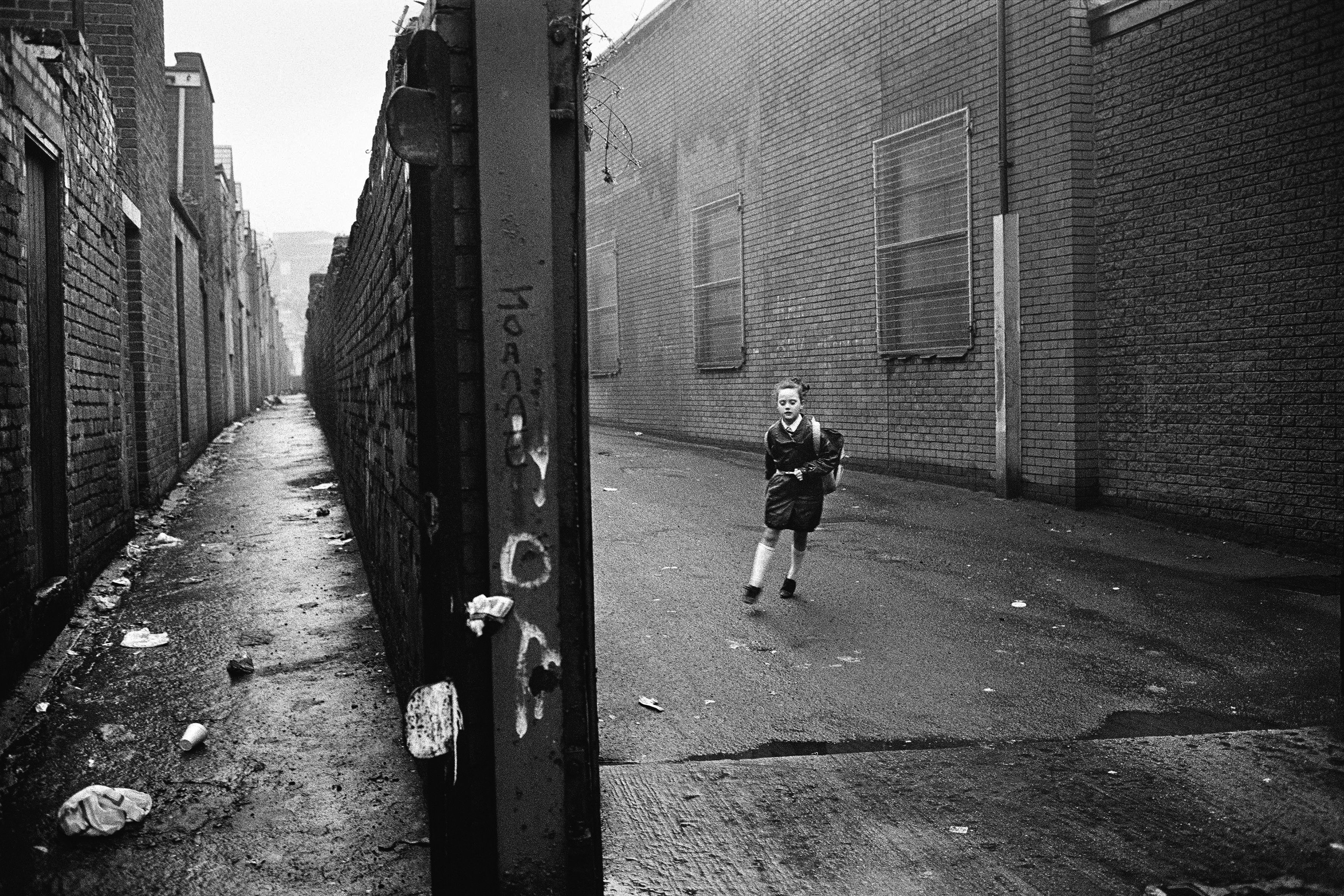

An opening page to the lavishly produced 'Belfast' tells us that the copyright for “text and images” rests with Krass Clement. But you will search in vain for text. He does not provide a single word: no captions, no names, no locations. Instead, he wishes his 112 black-and-white photographs to do the talking.

So, what do they say to us? First, and most obviously, given that they were all taken during a short visit in 1991, they remind us that Belfast has come a long way in 30 years.

These shots, beginning with the opening sequence of graveyard scenes, are bleak reminders of war and civic deprivation.

Unsmiling individuals stare into the lens against a background of unkempt urban streets, rubbish-strewn back alleys and graffitied walls. There is no light relief, even in the faces of children. Everywhere is desolation and, strangely in a city teeming with people, the overarching feeling is one of isolation.

📸

— Nathan Francis (@NathanFrancis__) August 4, 2022

‘The street is where everything unfolds’: #KrassClement’s unseen #Belfast – in pictures.

His new photobook is a mystical and melancholy time capsule. #Art #Photography

[https://t.co/uilOmHJlo0] pic.twitter.com/nwngybsezW

This is particularly so because he took many of photos in areas where new houses had been built on the outskirts, creating unlovely satellite suburbs that were colonising an inhospitable rural landscape. Even the dogs look unhappy in their new home.

Also betraying their unhappiness are the gun-toting squaddies who crouch beneath barbed-wire-topped walls. These obligatory shots of British soldiers on Belfast streets training their rifles at disinterested passers-by are surely a photographic cliché.

Rain – another cliché? – is ever-present. Bridesmaids lift their pretty dresses to run from car to church. Elderly women huddle beneath skimpy umbrellas for protection. Bare-headed, uniformed children walk to school, clutching their bags, heedless of the downpour. At least one of them was smiling.

Clement does not venture indoors, so we are not able to glimpse the inner life of the city’s residents. But one image, which I returned to several times, hints at both domestic pride and a desire to defy the grim exterior. On the sill of a lace-curtained window is a display of porcelain ornaments. It provides a welcome counterpoint to the sequence of soulless, rain-soaked streets.

The final pages return us to the cemetery. Visitors are dwarfed by giant crosses, their heads bent as they negotiate puddles to visit the grave, maybe the graves plural, of their departed relatives. Clement’s point, made without subtlety, is that death haunts Belfast.

'UNWELCOME': From 'Belfast'

Collectively, the images are suffused with gloom. Yet we know that Belfast at the time was engaged in the slow process of finding its way towards peace and hope for a better future. So, although his photographs do not lie, they do not tell the truth either.

That they reflect the joyless reality of a late winter in 1991 makes them historically interesting. Yet they have no relevance to 2022 and it is hard to understand why Clement and his publisher chose this time to present them to us. We learn nothing we do not know and everything that we wish to forget.

Indeed, and I am trying not to be unduly critical, they say a great deal more about Clement’s state of mind than they do about Belfast’s. He has admitted as much by observing that “all photography is, in a sense, a kind of self-portrait.”

In that same rare interview, he also agreed that his work is imbued with melancholia. “After all,” he said, “I come from Scandinavia, so it is a sort of second nature.”

Any of my photography friends familiar with Krass Clement ? Particularly the book Drum. Stayed with me once I’d seen it. What a photo can actually be. Anything you want.#photography #KrassClement pic.twitter.com/kZN8826sDq

— DAVID GLEAVE PHOTO (@dgleavephoto) May 19, 2019

Thank you for the honesty, but the imposition of your melancholy on a city coping with interminable sorrow cannot be other than unwelcome.

What is also odd is the fact that Clement’s depressing images are published in a format with the high-quality production values of a coffee table book. But the content is anything but eye candy.

Finally, I couldn’t help but contrast Clement’s work with that of Gilles Peress, whose photographs of Belfast I applauded in June last year. His had a relevance that is, sadly, lacking in this collection.

Belfast. Krass Clement. RRB Photobooks. £50.