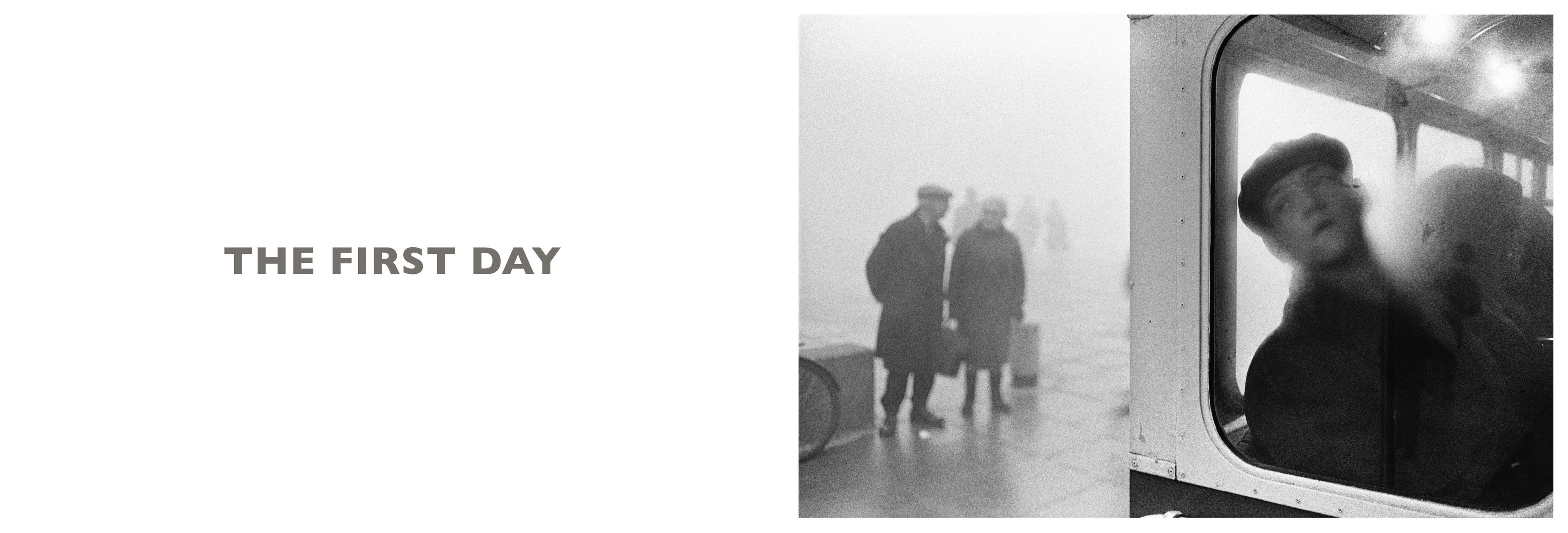

Whatever You Say, Say Nothing by Gilles Peress, and Annals of the North by Gilles Peress and Chris Klatell (£300). Published by Steidl. Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing: from the chapter, The First Day

I can see the beads of sweat on the courier’s forehead as he hauls a large box from his van to my door. A grunt, and he drops it gratefully at my feet. On the side, in large letters, it says: “Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.” I am baffled. I’ve been expecting a book with that title, but there must be some mistake. This is… well, what?

By the time I have lifted the box up to my flat, I am out of breath and this former tabloid journalist cannot help himself. As I reach for a penknife, I also reach for a pun. Must be a weighty tome, eh? Inside, immaculately packed, I find the “book”. It is three separate volumes, two of which are inside a decorated tote bag, plus an explanatory magazine and the publisher’s hard-covered promotional brochure. Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing: from the chapter, The First Day Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing: from the chapter, The First Day

Intrigued by the weight I lift them on to the scales: almost 12 kilos (26 lbs in old money). No expense has been spared. Two of them are large format productions, crafted on high quality paper and bound by a special technique that enables them to lay flat. These are not books, but objets d’art.

Again, before I tell you what’s inside, I need to introduce the author, Gilles Peress, French by birth, but long a resident in the United States. As a 26-year-old, in 1972, he was in Derry on Bloody Sunday, working for Magnum Photos. He witnessed the massacre, narrowly missed being shot, and took the pictures of 31-year-old Paddy Doherty moments before he was killed while trying to crawl to safety in front of the Rossville flats. Pictures that helped to prove Paddy’s innocence.

Peress, now professor of human rights and photography at a private New York college, returned to Ireland in 1979, and was also around at the beginning of the 1981 hunger strike, to take many hundreds of pictures, the kind that rarely, if ever, appeared in the newspapers of the time. He has collated the results, 979 photographs, almost all in black and white, in this gargantuan double volume running to more than a thousand pages with barely seventy words of text.

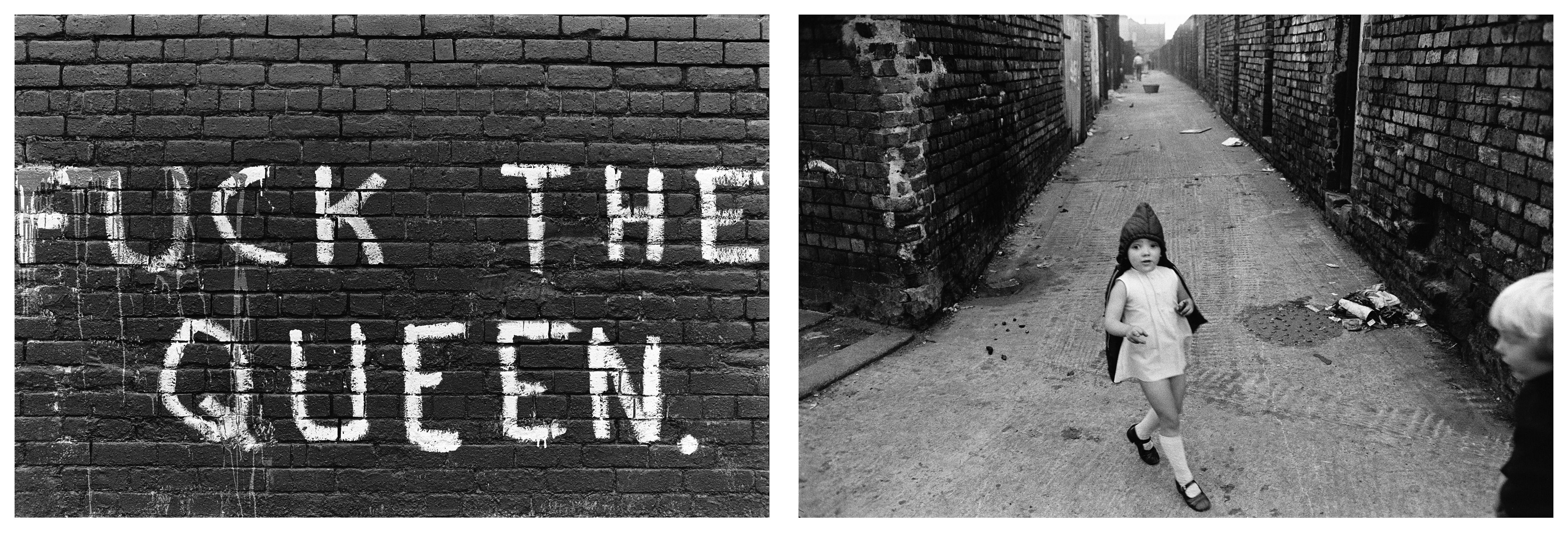

He calls Whatever You Say, Say Nothing a work of “documentary fiction”, an attempt to portray – or, as he prefers, “to articulate” – the unfolding of people’s lives throughout a seemingly never-ending conflict. It is not chronological, or even logical, but it is strangely fascinating to turn the pages and take a sort of behind-the-scenes look at our history. Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing: from the chapter, The First Day

Volume One opens with a sky darkened by a murmuration of starlings followed by a glimpse of rural beauty and a burst of urban squalor in 1970s Derry. A long sequence of Apprentice Boys’ marchers, with scenes of piety, drunkeness and clumsy smooching, leads into the horror of Bloody Sunday. Down the years, we think we have got used to these images, but they still retain the power to shock.

Then there is a surreal shot of two rifle-toting British soldiers stretched out in a front garden watched from the doorway by a gaggle of young boys as an auld fella sits unconcernedly reading his newspaper. Even as lives are taken, life goes on.

Skipping forward ten years, our attention is grabbed by wall art and the graffiti marking the heroic sacrifice of Bobby Sands and his hunger-striking comrades. The familiar sights – bonfires, balaclavas, bin lids, youthful bravado and bad haircuts – are juxtaposed with a tableau of sporting activities: a cricket match, bowls and riding to hounds. Bizarre as well to see the 1981 Miss Belfast winner pictured atop the Europa, the world’s most bombed hotel.

Volume Two is dominated by death, an explicit representation of Peress’s accompanying statement about the book being “dedicated to the victims of the conflict and their families.” Here are haunting images of funerals, graveyards and the blank faces of the bereaved. Another thread, which runs throughout both volumes, displays non-events, “where nothing happens”, those so-called “boring days”. But I couldn’t help but groan at a section featuring a photo of Ian Paisley at a microphone, inappropriately headlined “The Day They Say No.” Days surely? Day after day. Year after no-surrendering year. Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing: from the chapter, The First Day

Having failed on the first read-through to find a unifying meaning to the collection, I scanned the pictures a second time and came to accept that there is no single theme. That clearly wasn’t Peress’s intention. He is at pains to tell us what the book is not. Neither art nor journalism but, just maybe, in some space between.

“I wanted to do work that is beyond categories, in a no-man’s land beyond labels,” he writes. So he prefers to call it “an experiment in visual language using photographs.” It is such a unique, possibly unprecedented, approach to Ireland’s troubles that it cannot be compared to anything else. It stands alone. Unconventional, ambitious, a touch crazy. A vanity project possibly, but one with a special resonance to the communities of Belfast and Derry.

THE MEMORABILIA OF STRUGGLE

And then there is Annals of the North, 904 pages with more than 200 photos, and interwoven with illustrations, maps, charts, documents, essays and lists, the memorabilia of struggle. Peress calls it an almanac rather than an academic history. Again, although there is a welter of information, it is deliberately lacking in a coherent chronology.

This book (which can be bought separately for £65) is complementary to Whatever You Say, Say Nothing. I found it something of a hotch-potch, but with odd moments of insight. There is another lengthy section on Donaldson as Peress explores the motivations of his late friend. From villain to hero, we also come across excerpts from Bobby Sands’s prison diary.

Some of the documents have a very modern relevance indeed. For example, a letter sent in 1980 by the then attorney-general Michael Havers to the defence minister, Francis Pym, is eye-opening. Havers, who was concerned about the “increasing number of incidents” where firearms were being used at vehicle checkpoints, wrote: “My anxiety is that sooner or later we may have to institute criminal proceedings against a member or members of the security forces.”

As kids in 1972, we invited 2 French photographers into our Ramoan Gdns home. They were shooting IRA foot patrol in snow — pics are famous. I only realised 2day that 1 of snappers was Gilles Peress. 'A lensman's extravagant show of affection' https://t.co/v6tD0puNqR @molloy1916 pic.twitter.com/j35w3AYJVk

— Máirtín Ó Muilleoir (@newbelfast) June 1, 2021

Three anecdotes stand out. The first involves Peress witnessing Martin McGuinness as he organised the funeral of one of the three Provisional volunteers shot by the army in Strabane in February 1985. Aware that the army was closing in to prevent a proper republican funeral, Martin improvised and Peress was able to record the ritual volley over the casket.

The second involves him drinking with the Sunday Times’s reporter, Murray Sayle, who filed copy stating unequivocally that the parachute regiment had murdered innocents on Bloody Sunday in a “special operation that went disastrously wrong.” The paper refused to publish his story and he quit.

And the third is very personal. After Peress had photographed Paddy Doherty’s murder, he realised the army might confiscate his film. He spotted a tall blonde standing with her friends, still in shock from the shootings. He mumbled his fears to her, handed her six canisters of film, all of which she quickly concealed in her underwear. He arranged to see her that evening at a hotel. She arrived as promised and he sped off into the night to drive to Dublin airport, sending his sensational photos safely to Paris. He never saw the girl again.