Conrad Atkinson (82), the only artist to have his work banned at the Ulster Museum, has passed away at his home in Boustead Hill, Cumbria, England.

In 1978, porters at the Ulster Museum refused to hang his hard-hitting work on Queen Elizabeth's Silver Jubilee - Silver Liberties - because it consisted of large canvasses in the colours of the Irish tricolour highlighting the Bloody Sunday slaughter. A fourth panel in black showed victims of police brutality in English prisons – Conrad's prescient warning that violations of civil rights on the streets of Belfast would ultimately lead to injustice on the streets of Bristol and Brighton.

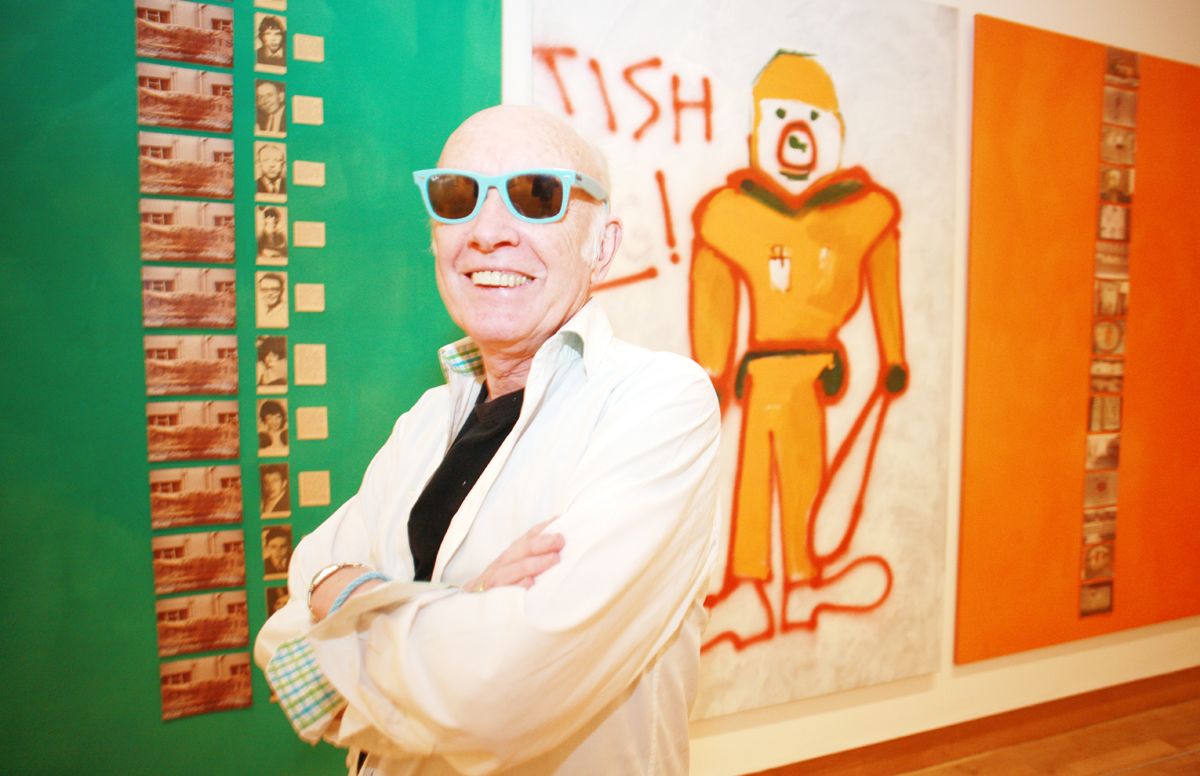

POP-PUNK: Conrad Atkinson pictured in his Cumbrian home earlier this year

Silver Liberties finally found a home in the Northern Ireland collection of the Wolverhampton Art Gallery among other striking Troubles artworks by Conrad. Unsurprisingly, his works were never included in the official government collections of the period, prompting his wry comment: "No-one ever got rich painting Northern Ireland."

Sad to hear #artist Conrad Atkinson (b1940) in #cleatormoor #CUMBRIA

— Alexatours❤Cumbria (@Heritarcumbria) October 9, 2022

has passed away #RIP

He created the Miner, the Phoenix & the Hand as a memorial to the town’s once thriving mining industry.

More info⤵️https://t.co/wwUsxhzxsj pic.twitter.com/b44JmStnaJ

Following the mid-nineties ceasefires, however, interest in his work soared as curators sought out the few artists who had turned a withering eye on state policy in the North.

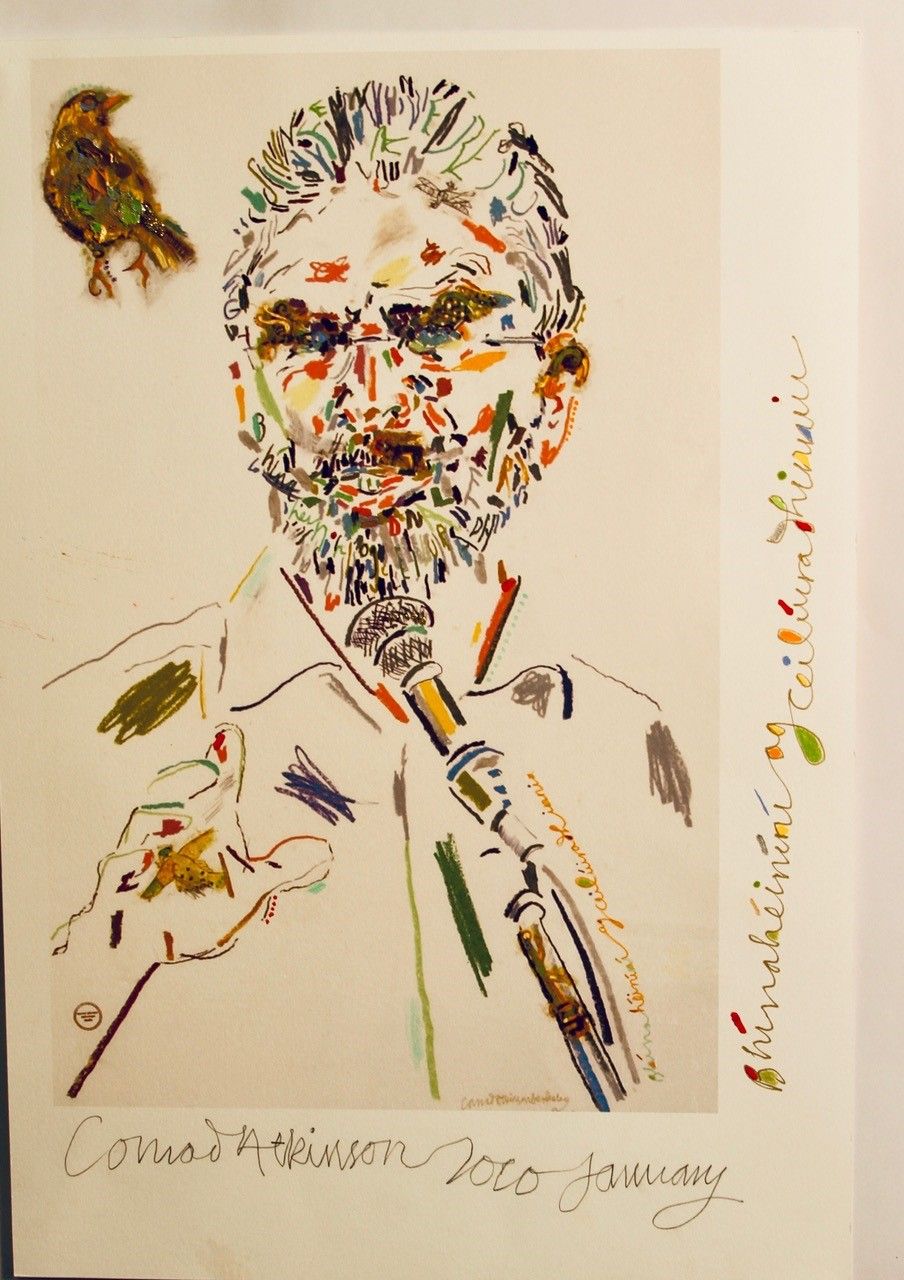

UNIQUE: Gerry Adams as seen by Conrad Atkinson

His sparkling portrait of Gerry Adams, complete with quotes from Bobby Sands' diary and birds from the Book of Kells, is now in the Tate collection with a smaller version hanging in Hillsborough Castle.

Conrad highlighted the woes of working class people throughout this career, taking on asbestos poisoning in his 'Lungs of Capitalism' and the obscenity of landmines in his Madonna-adorned explosive devices which once covered a floor of the High Gallery in Atlanta, Georgia.

His commitment to justice in Ireland was undoubtedly linked to his own background. Raised a Catholic in Cleator Moor - Cumbria’s 'Little Ireland' - the country of his forebears was never far from his thoughts. Uniquely among his radical peers, however, he travelled to Belfast and Derry in the early seventies, determined to breach the blanket censorship with his artworks. He subsequently used the bloodstained civil rights banner from Bloody Sunday and painted handkerchiefs from Long Kesh in his works. He collaborated closely with trade unions in Belfast in the early seventies, proposing the then derided ideas of a ceasefire — which he thought wholly possible based on his interviews with Sandy Row paramilitaries — and political talks at a time such suggestions were dismissed out-of-hand by the powers-that-be. His exhibition 'A Shade of Green, An Orange Edge' in Belfast in 1975 was the first time the war on our streets was addressed in a gallery.

Cleator Moor artist, Conrad Atkinson passes awayhttps://t.co/RtnOu9njoz

— LittleIreland 🇬🇧 (@LittleIrelandUK) October 9, 2022

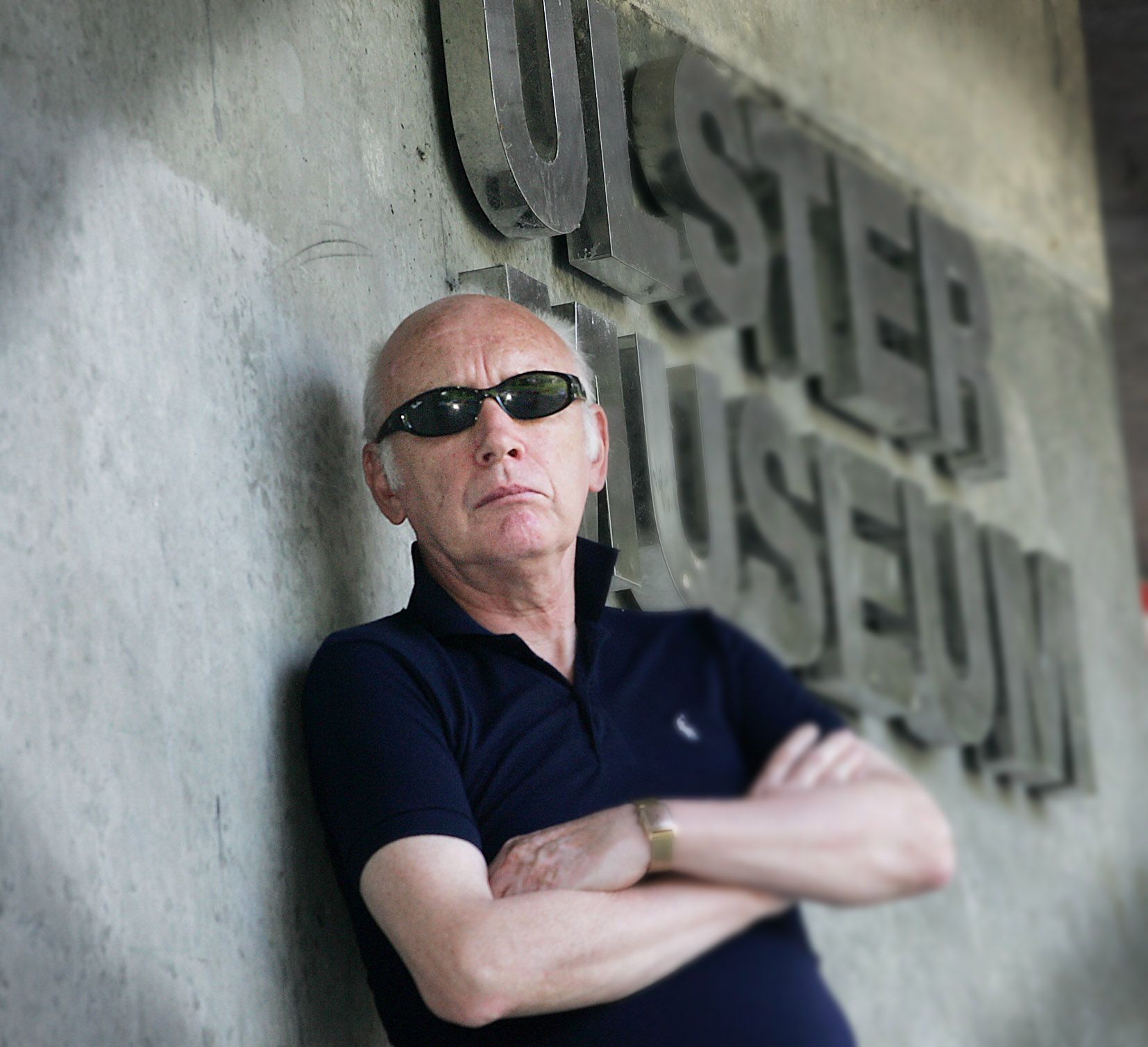

In 2006, Conrad was invited back to Belfast and commissioned to create works on the evolving peace and reconciliation process. The result, 'Some Wounds Healing, Some Birds Singing' was exhibited in the Grand Opera House, Belfast, in 2007 and included his evocative 'New Northern Ireland Wallpaper' which covered an entire wall in the makeshift gallery. That piece was subsequently acquired by the Arts Council of NI, a move which in turn enabled the Ulster Museum to stage a show of the Wolverhampton Art Gallery Northern Ireland works. Thus, Silver Liberties, after first being shown in the Golden Thread Gallery in 2012, finally made it on to the walls of the South Belfast institution in 2014, much to the delight of Conrad.

WOUNDED: Conrad Atkinson at his 'Some Wounds Healing, Some Birds Singing' exhibition in 2007 with Paul Denvir who agreed to have his wound depicted in the paintings

During this many trips to Belfast, he was crystal clear in the need for art to help the healing process post-conflict. "Art definitely has a role to play in the process," he said. "It can be very cathartic emotionally and in Northern Ireland it needs proper funding."

Conrad Atkinson: "you never know what art is for." #art #solidarity #equality #representation #RepresentationMatters pic.twitter.com/5CMs0jTWs3

— Alexandra Lazar (@thundermoth) September 8, 2016

Latterly, with his sight failing, Conrad retired from his position as Professor Emeritus at the University of California Davis. However, he continued to produce works and his long career was celebrated globally on his 80th birthday in 2020 – though Covid upended plans to display one of his works in Belfast City Airport.

Critics acknowledged his trailblazing role in linking the world of art to the struggles of everyday people. "It is the forging together of conceptualism and activism to art practice that distinguishes Atkinson's work and makes it such an important contribution to 20th century art history," said Lawrence Rinder, Dean of the California College of Arts.

Of recent years, #ConradAtkinson 😪had been losing his sight - quite blow for anybody never mind an artist - but his spirits remained high & his passion for Ireland & its people unquenched. Belfast lensman Frankie Quinn caught up with him as part of his series on Little Ireland pic.twitter.com/E1Bzrtmp5a

— Máirtín Ó Muilleoir (@newbelfast) October 9, 2022

Recently, Conrad has been supportive of Belfast lensman Frankie Quinn, who was engaged in a major work on the Irish heritage of Cleator Moor. Frankie photographed the artist in his home earlier this year (above).

IN THE FRAME: Conrad Atkinson at the Ulster Museum in 2007

Conrad Atkinson is survived by his wife, Margaret Harrison, herself a renowned artist, ("I'm not even the most famous artist in Cumbria," Conrad would joke after Margaret won the coveted Northern Prize) and two daughters.

Leaba i measc na naomh go raibh aige.

On this day 5 years ago - the launch event for the Vallum Gallery with a very busy opening night & a fantastic speech from Professor Conrad Atkinson - great to see his & Margaret Harrison's art work celebrated where they began their illustrious artistic careers - local to global. pic.twitter.com/3AlCQgU5gC

— The Vallum Gallery (@VallumGallery) September 25, 2020