SQUINTER must say he enjoyed the Belfast Telegraph’s colourful online picture special on the Easter Monday Apprentice Boys parades across This Here Pravince.

History, spectacle, vibrancy – it was all there and Squinter was about to email the picture desk to congratulate them on a job well done when he came across this picture (right). The Billy Boys Flute Band Rathcoole, are one of the newer additions to the Belfast band scene, having been formed as recently as 2018.

But what, Squinter wondered as he looked out the window, into the distance and scratched his chin, is a band called the Billy Boys doing in a celebratory picture special beside children eating ice-cream and OAPs sitting in deckchairs with tartan blankets round their knees?

For the Billy Boys are not followers of the legendary Glasgow comic Billy Connolly. They are not admirers of the Wild West icon Billy the Kid. The big drum is not a homage to the crooner Billy Joel and band members are not fans of comedy actor Billy Crystal. The Billy they’re saluting was a bloke called Billy Fullerton, leader of a notorious Protestant razor gang in the 1920s which toured the Bridgeton area of Glasgow slashing the faces of any Catholics they happened to run into. There’s a suggestion that the name Billy was taken from King Billy and that the fact that its leader was a Billy also was a mere coincidence.

Hmm. You pays yer money…

The gang is paid tribute to in the most famous chant in the Rangers songbook, The Billy Boys.

Hello, hello, it’s the only song we know…

No, sorry, wrong words. Just a second…

Hello, hello, we are the Billy Boys,

Hello, hello, you’ll know us by our noise,

We’re up to our knees in Fenian blood,

Surrender or you’ll die,

For we are the Bridgeton Billy Boys.

Got a certain ring to it, no?

Billy the charmer was a member of the British Union of Fascists whose most notable act of fascist-flavoured fortitude was attacking striking workers during the 1926 General Strike. It's an integral part of the inspirational Easter story, isn’t it? Christ is condemned and crucified, rises triumphantly and ascends into Heaven accompanied by a flute band playing songs about slashing Fenians and wading in blood.

In defence of the Billy Boys Flute Band Rathcoole, an indignant loyalist tweeted Squinter to take issue with the Billy Boys narrative. “That’s not the present day usage of the Billy Boys, but you know that. You’ll be claiming that Rangers players pull their socks up over their knees to signify blood.”

The bloke didn’t say what the present-day usage of the Billy Boys is, but Squinter’s happy to accept that it’s something to do with food banks or charity walks. After all, the Shankill Sons of Jack the Ripper Flute Band don’t mean any offence by their either. Victorian London was a long, long time ago – and people do forget.

Neutral is as neutral does

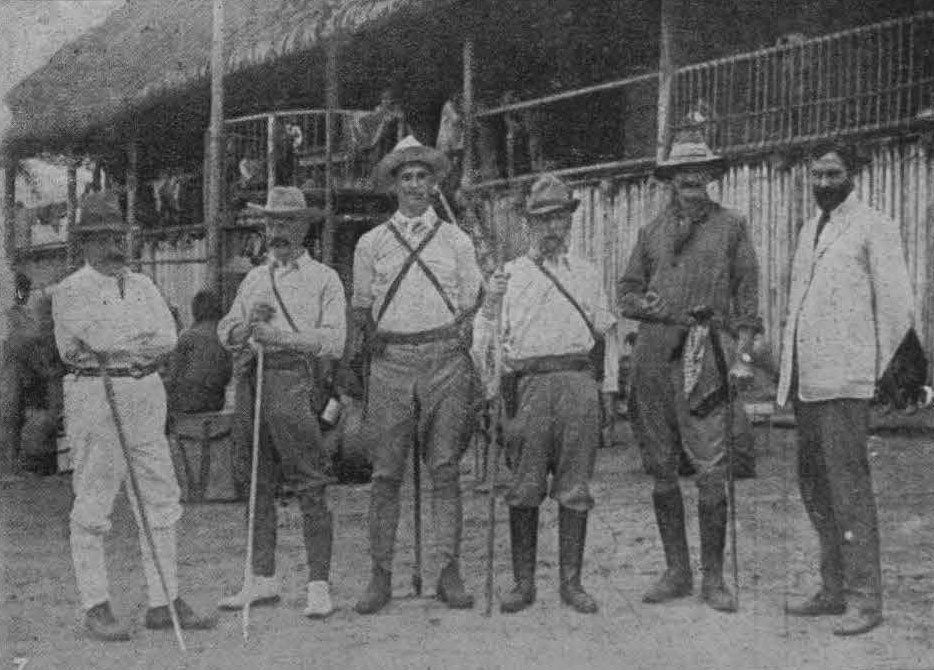

ATROCITIES: Roger Casement (right) in the Belgian Congo

FIANNA Fáil and Fine Gael seem to have decided that the best way to counter Sinn Féin’s rise in the polls is not to do something about the housing and health crises or anything else as complicated and difficult as that. They reckon the old order can be restored by acting hard.

So it is that a consensus has emerged that Ireland remaining neutral is a dereliction of duty; that with the Russian invasion of Ukraine continuing it is no longer acceptable for Ireland to benefit from the strength of NATO without being a member. It’s time to pull on the boots, don the flak jacket and lock and load.

The difficulty is that this consensus has emerged only in the pages and on the airwaves of Ireland’s deeply conservative media. While the rugby dads and the Dalkey mums on the school run in their SUVs cheer every time a call to arms is made, among the general population support for continued neutrality is extremely strong. An Irish Times poll last week showing that fully two-thirds of the population don’t want anything to do with NATO.

It's estimated that Ireland signing up to NATO would entail increased military spending of around €4.3bn a year, and even that vast sum would made Ireland a sprick in the NATO pond. (And let’s set aside the fact that a fraction of that sum would go a long way to fixing the housing crisis.) Neutrality is, of course. one of Ireland’s most precious resources. Ireland has been the victim of colonialism, it has never attacked another country, and its attitude to militarism is informed by that history. That gives the country a standing in the world way out of proportion to its size and importance.

Unfortunately a cash sum can’t be put on neutrality and for that very reason it is disdained by the gombeen men and the gurriers of FF/FG, who choose their friends by the amount of flats they’re renting out in Dublin and the money they’re willing to pay to entertain them at the Galway Races. So nebulous is the idea of Irish neutrality that it can never be explained in terms of statistics and numbers – and so an anecdote might serve us better…

About five years ago Squinter’s sitting in the bar of his hotel in Cibitoke, Burundi, east Africa. It’s chucking it down outside and with a cold beer and a book it should be a cosy and comforting scene, but there’s one big problem: the humidity. The sweat’s pouring down Squinter’s forehead and ribs. Every five seconds Squinter raises a white handkerchief to wipe his head and face and as soon as the cloth is removed the sweat pops instantly. A fairly clichéd colonial image, you might say – white, middle-aged bloke sitting in a bar, suffering in the heat.

Standing at the bar is a group of six or eight young local men, tipsily conversing in Kirundi, the country’s first language. When Squinter goes to the bar for another beer they engage Squinter in French, the second language of Burundi. “Vous êtes, d’où, mon ami?” “Where you from, chum?” Squinter tells them he’s Irish and we get to talking a bit more. They nod their heads when Squinter tells them he’s a reporter checking out the aid work of Concern, and after a bit of chat about the heat and humidity, Squinter returns to his table.

Slowly but surely the atmosphere begins to change and an increasing amount of over-shoulder glances in his direction suggest that Squinter’s the reason. This is confirmed when one eventually shouts over: “Eh, vous êtes Belge, non?” “You’re Belgian, aren’t you.” Squinter smiles. “Non, je suis Irlandais, comme j’ai dit.” “No, I told yiz lads, I’m Irish.” This is considered for a few seconds before another calls: “Où est vot’ passeport?” “Where’s your passport?” And when Squinter tells them it’s in his room he senses that’s exactly the evasive answer they expected.

A pause for a bit of background history. Burundi neighbours the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly the Belgian Congo. Roger Casement sprang to prominence through his courageous exposé of the sickening atrocities committed on native workers in the rubber plantations in Congo. Belgium also ruled Burundi and committed equally heinous acts of barbarism there, something for which Burundi is currently claiming €36 billion in reparations from Belgium and Germany.

As is the case in so many countries, the former coloniser maintains a significant economic interest in the country and there is significant tension between Burundians and Belgians.

Back in the bar and the very nice barwoman intervenes to ask the young men to leave Squinter alone and in a few minutes the interpreter who is accompanying the Concern group arrives to calm things down and she and Squinter leave. Turns out that the group at the bar were off-duty militiamen on a night out. Further turns out that Belgians in Burundi are unsurprisingly loath to admit to being Belgian in conversation and often they’ll claim to be Irish. This is what the militiamen were getting aerated about.

Belgians don’t claim to be British, or French, or Norwegian, or Estonian – they claim to be Irish because, as is the case in many other countries in Africa and elsewhere across the world, the Irish are ‘well got’, as the saying goes. And they’re well got because they are known not for their military exploits or their tendency to invade and rob other countries; they’re well got because their history of neutrality gives them a disproportionate prominence in the field of international aid.

There can’t be many people holding an Irish passport who don’t have positive stories to tell about the benefits it confers in terms of goodwill. That’s unlikely to change in the lifetime of anyone reading this, but how utterly reckless would it be for Irish people in 2022 to deny future generations that global reputation which has been in the making for a century and more?