Once in a lifetime – perhaps twice if you’re lucky – you will finish a book and turn it upside down, flick through its pages deck-of-cards-style, shake it by its spine and even subject it to the sniff test, all in a bid to try to work out what magic it possessed to knock you into a cocked hat. Where did it get its power from; how did it perform that act of literary wizardry?

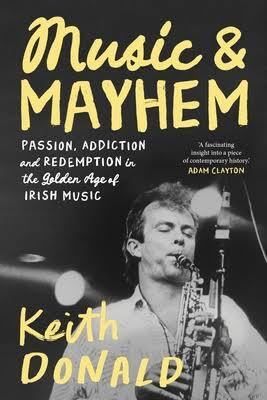

Such a book is Milkman.

A landmark opus from a war-torn Belfast where the Lord in His mercy is, thankfully, looking down, Milkman is the redeeming antidote to the warehouses of insufferable prattling passing as ‘Troubles’ tomes.

In fact, not content with creating a story both shocking and comforting in its recreation of seventies Ardoyne, the incredible talent that is North Belfast author Anna Burns has birthed a completely unique and novel style of story-telling. They’ve been committing stories to paper (not to mention vellum and cowhide) on this island for 1,200 years and counting but until now no-one came up with the provocative, unsettling idea of having a 350-page yarn without naming any of the protagonists – or places.

Not even the compelling focus of this extraordinary story, a glorious young woman besotted with books who is caught up in the madness of war. Is there any other type of war? Not if you revere the anti-war masterpieces of those literary giants Tim O’Brien, Kurt Vonnegut or or Joseph Heller, author of Catch 22, whose breath imbues this work.

Indeed, in its irreverence and boisterousness Milkman is like the icing of Mr Heller’s upside down world layered onto a sumptious and side-splitting sponge cake of Flann O’Brien meets Puckoon.

The dramatis personae are recognisable to anyone who grew up in the hardbitten heartlands of republican Belfast as nothing more mysterious than our neighbours: Somebody McSomebody, Eldest Sister, Maybe-Boyfriend, Third-Brother-In-Law, Nuclear Boy, Ma and Da, and Tablets Girl ("the girl who was really a woman who went around putting poison in drinks”). This sympathetically-portrayed, manic crew populate a besieged and beleaguered landscape where bomb-makers and bookmakers are all part of the one chaotic community — none more pass-remarkable than the other.

Our teenage hero navigates this treacherous terrain deftly, her nose stuck in a book even as she perambulates the district, until she attracts the attention of Milkman, an IRA leader turned frightening stalker. At least, we think he is an IRA leader as if he is in the IRA, no-one would know as it’s a secret organisation of ‘renouncers-of-the-state’?

There is no black and white here of ‘Troubles' literature: the IRA are no more the villains than the security farces the heroes. Indeed, the only people who get a worse press in Milkman than the “local boys" are the police, who are so distrusted that they are only called into the area by people who are intent on ambushing them, and the soldiers who (shades of seventies Lenadoon) slay all the local dogs whose barking had alerted the renouncers.

What we now call collusion — though in the seventies it was a word which had not yet entered the lexicon — gets a deft touch:

“Eventually the state responded by admitting that yes, it had precision-targeted a few accidental people in pursuance of intended people, that mistakes had been made, that that had been regrettable, but that the past should be put behind, that there was no point in dwelling. Most of all, in spite of target error and the unforeseen human factor, it reassured all right-thinking people that they could rest easy… that a leading terrorist-renouncer had permanently been got out of the way. ‘Not to get into equivocation or rhetorical stunts or sly debater tricks or savage glee,’ said their front-of-shop man, ‘but we consider this a job well done.’"

Everything is here in an accurate, honest, unvarnished depiction of the way we were: a band of feminists who attract the wary eye of the renouncers, pious spinsters chasing the finest man in the neighbourhood whose honourable profession is, in fact, that of milkman, and every social situation which requires leaving the suffocating confines of ‘our area' a veritable minefield.

All is at once clear and obscure — just as on the battlefield. And this fractured city where the Pope is memorably invited to copulate on gable walls is captured perfectly in all its normal craziness.

“Matters didn’t stop at ‘their names’ and ‘our names’, at ‘us’ and ‘them’, at ‘our community’ and ‘their community’, at ‘over the road’, ‘over the water’, ‘over the border’. Other issues had similar directives attaching as well. There were neutral television programmes which could hail from ‘over the water’ or from ‘over the border’ yet be watched by everyone ‘this side of the road’ as well as ‘that side of the road’ without causing disloyalty in either community. Then there were programmes that could be watched without treason by one side while hated and detested ‘across the road’ on the other side. There were television licence inspectors, census collectors, civilians working in non-civilian environments and public servants all tolerated in one community whilst shot to death if putting a toe in the other community. There was food and drink. The right butter. The wrong butter. The tea of allegiance. The tea of betrayal.”

So fair play and maximum respect to you, Anna Burns of Ardoyne, for writing this stunning work of beauty and briliance.

If Hunger is the greatest movie about our three-decade nightmare, Butcher’s Dozen the greatest poem, Silver Liberties by Conrad Atkinson the greatest work of visual art; then this astonishing work, this Milkman which I am continuing to turn over in my hand to try to unlock its genius, is the greatest novel.

Milkman is the Man Booker Prize winner of 2018. Faber & Faber. £8:99 from No Alibis, Botanic Avenue, and all bookshops worthy of the name.