ON April 1, 1970, the Ulster Defence Regiment of the British Army formally took its place in the ranks of the British Army. The UDR was a locally-recruited militia established by the British Government following its disbandment of the B-Specials the previous year. When it too was disbanded 22 years later it had achieved an even greater level of sectarian notoriety than the Specials.

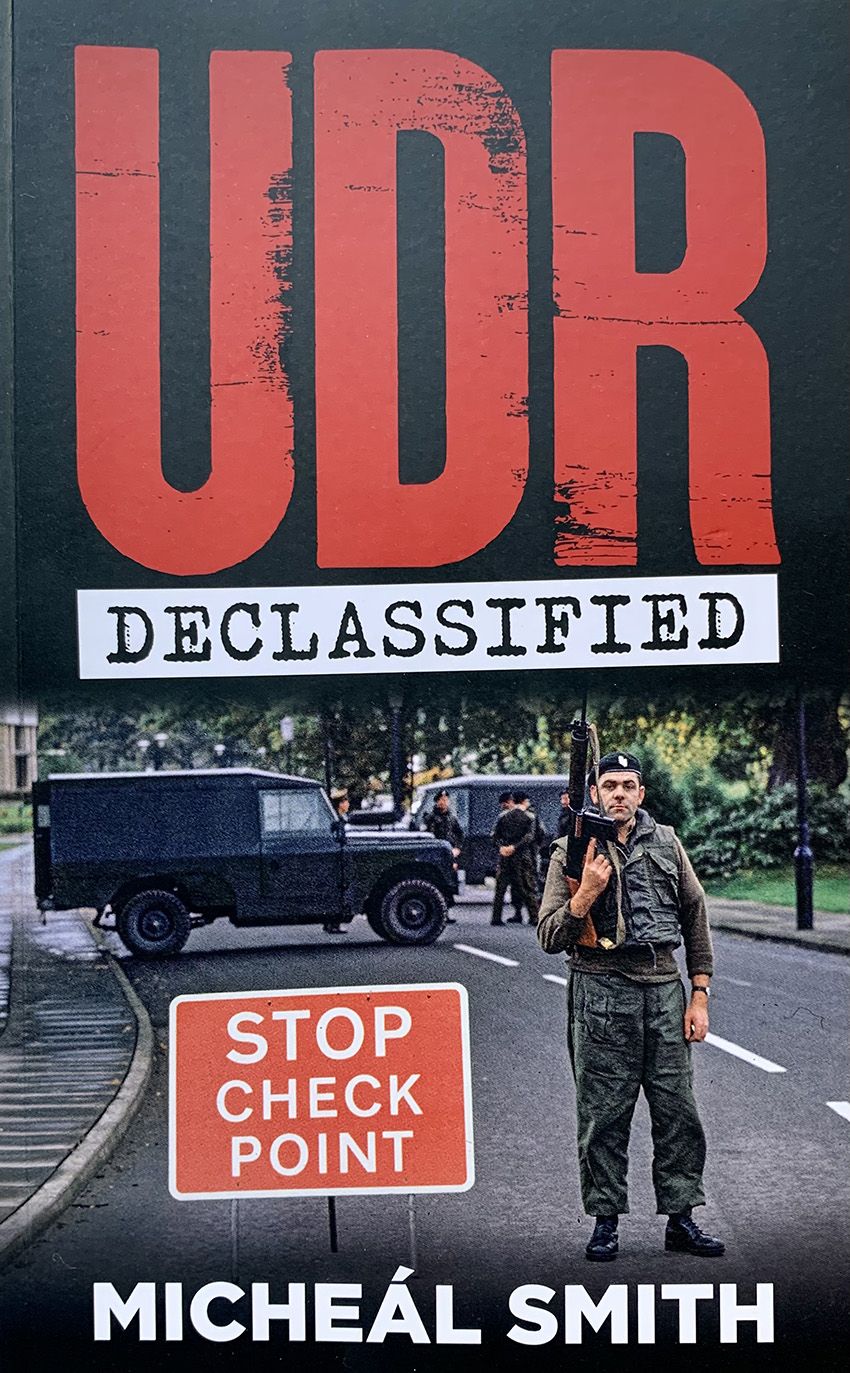

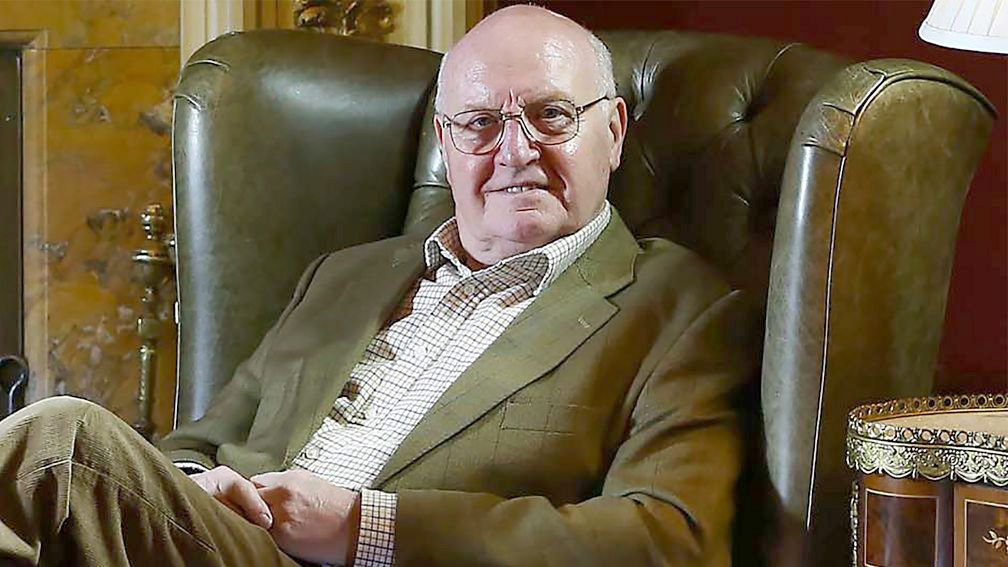

Micheál Smith, who is an advocacy case worker with the Pat Finucane Centre, and who previously worked as a diplomat in the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin, has just published ‘UDR Declassified’ – an account of the British Army regiment which looks at the “background to the regiment and the traditions from which it was born...” The book also examines “the range of illegal, collusive and murderous acts of some of its numbers...”

Smith describes the book as being “not a history of the regiment” rather “an attempt to tell what Whitehall, Number 10 and the MoD had to say about the regiment in papers found among declassified files.”

The British Government was warned of the dangers of establishing the UDR. The Ulster Special Constabulary – the B-Specials – had been a unionist paramilitary militia renowned for its sectarian and violent actions against the nationalist people of the North. It was, along with the RUC, the armed wing of the unionist state from partition.

In 1969 the B-Specials played a leading role in attacks on civil rights demonstrators and during the pogroms in Belfast which saw people killed, hundreds of Catholics homes destroyed and thousands forced to flee as refugees. The Hunt report in October 1969 called for its disbandment and the creation of a new force.

Concern among unionists at the disbandment of the B-Specials was assuaged by unionist leaders. Stormont Prime Minister Chichester Clark said on October 13, 1969: “The name and organisation of the Specials will change... our new security reserve will have the arms and other equipment it needs to be a highly effective defence force, not for the conditions of ’21 for the ’70s.”

The UDR was established on January 1, 1970, and became operational on April 1. By the end of March 1, 420 of the 2,440 recruits into the UDR were former members of the B-Specials. In some areas whole platoons of the Specials joined the UDR en masse.

Within a very short time its reputation for sectarianism had exceeded that of the B Specials. In addition, as Smith acknowledges: “For elements of the British establishment the UDR was used as a surrogate ‘counter-gang... the Ministry of Defence (MoD) knew UDR weapons were systematically stolen and used to murder Catholics… the British were in fact well aware of what was going on and frequently referred to it internally as ‘collusion’ from the early 1970s.”

In the first ten years of its existence, over 200 members of the UDR were convicted of offences, many relating to sectarian murders. Smith reports how in 1976 Hibernia magazine had catalogued a list of more than 100 UDR soldiers charged with crimes. He also notes how an internal investigation into 10 UDR based at Girdwood Barracks in North Belfast concluded that “up to 70 members of the battalion had links to loyalist paramilitary groups at some level, while it was also suspected that up to 30 members of the battalion had engaged in large scale fraud, claiming an estimated £30k-£47k for duties not carried out. This money was strongly suspect of being passed to the local UVF.”

UDR soldiers also formed part of the Glenanne Gang, which operated out of a farm in Armagh owned by James Mitchell. It was responsible for over 120 killings, and scores of injuries, including the Dublin and Monaghan bombs in May 1974 which killed 33 people. Sometimes the involvement of UDR soldiers was down to the individual, but frequently it was part of a structured process of control and collusion by elements of the RUC, the RUC Special Branch and the various British security agencies, including the Force Reconnaissance Unit, MI5 and MI6.

A 1984 issue of Ulster – the UDA magazine – listed 41 lifers belonging to the organisation in Long Kesh. 24 of the 41 UDA lifers “came from the security forces, five from the UDR.”

Smith concludes that the UDR “functioned as a facility for loyalist groups within which paramilitaries had access to military training and equipment... there was also a steady traffic of weaponry and intelligence data from UDR personnel and bases into the waiting arms of loyalist paramilitary groups. This weaponry and intelligence was used repeatedly to kill Catholic civilians.” He also states that Whitehall, the NIO and the MoD knew there was collusion both in weapons thefts and in murderous attacks but “combating such collusion was never a priority... For many people, the UDR was simply the B-Specials with better weapons.”

UDR Declassified is a hugely informative account of a part of the conflict and of the role of the Ulster Defence Regiment, which generally gets scant mention today. The forensic examination of declassified documents by Smith and others has already resulted in similar publications, including Anne Cadwallader’s ‘Lethal Allies’ and Margaret Urwins ‘A State in Denial’. Tens of thousands of such files still remain hidden by the British state and wait to be uncovered and examined. Some, like those relating to the killing of two children by plastic bullets – Paul Whitters and Julie Livingstone – remain closed for another 40 years. The reason for this and the rationale behind the British Government’s amnesty proposals to end conflict-related prosecutions is to ensure that the truth about Britain’s role in the war remains hidden.

Micheál Smith says: “The denial of access to history is a part of a continuum of British state efforts to obscure its colonial past – to protect the reputation of the British state of generations earlier, concealing and manipulating history – sculpting an official narrative in a manner more associated with a dictatorship than with a mature and confident democracy.”

UDR Declassified by Micheál Smith published by Merrion Press.

Covid has reacquainted me with my Long Kesh radio days

SUNDAY CLUB: John Bennett

I LISTEN to the radio a lot. I always have. I’m more of a wireless listener than a television viewer. Raidió na Gaeltachta, Raidió Fáilte, RTÉ Radio 1 and Lyric FM. And Radio Ulster. Covid has reunited me with the radio. It was just like being back in Long Kesh.

I am a long-standing fan of John Bennett’s Sunday Club. His music selections match my tastes as do his dulcet tones as sleep beckons. Many a time he lulled me to sleep in my lonely cell.

When I was in Long Kesh Downtown Radio was a favoured station, particularly Tommy Sands’ programmes. The request shows were always a favourite, regardless of the station. The unsuspecting presenter would cause ructions in our wing after lock-up when he or she read out: “Best wishes to wee Mickey who is away from home for a while. Best wishes from Sadie, his everlasting sweetheart.”

Or “ Happy birthday Walter from your mammy. We are having a big party for you.”

I wonder did they ever guess that their requests were for long-suffering political prisoners? And sometimes from other long-suffering political prisoners pretending to be mammies or sweethearts. Poor wee Mickey. Walter bocht.

I used to love Gerry Anderson and Seán Coyle on Radio Foyle. Free spirits. Brilliant broadcasting.