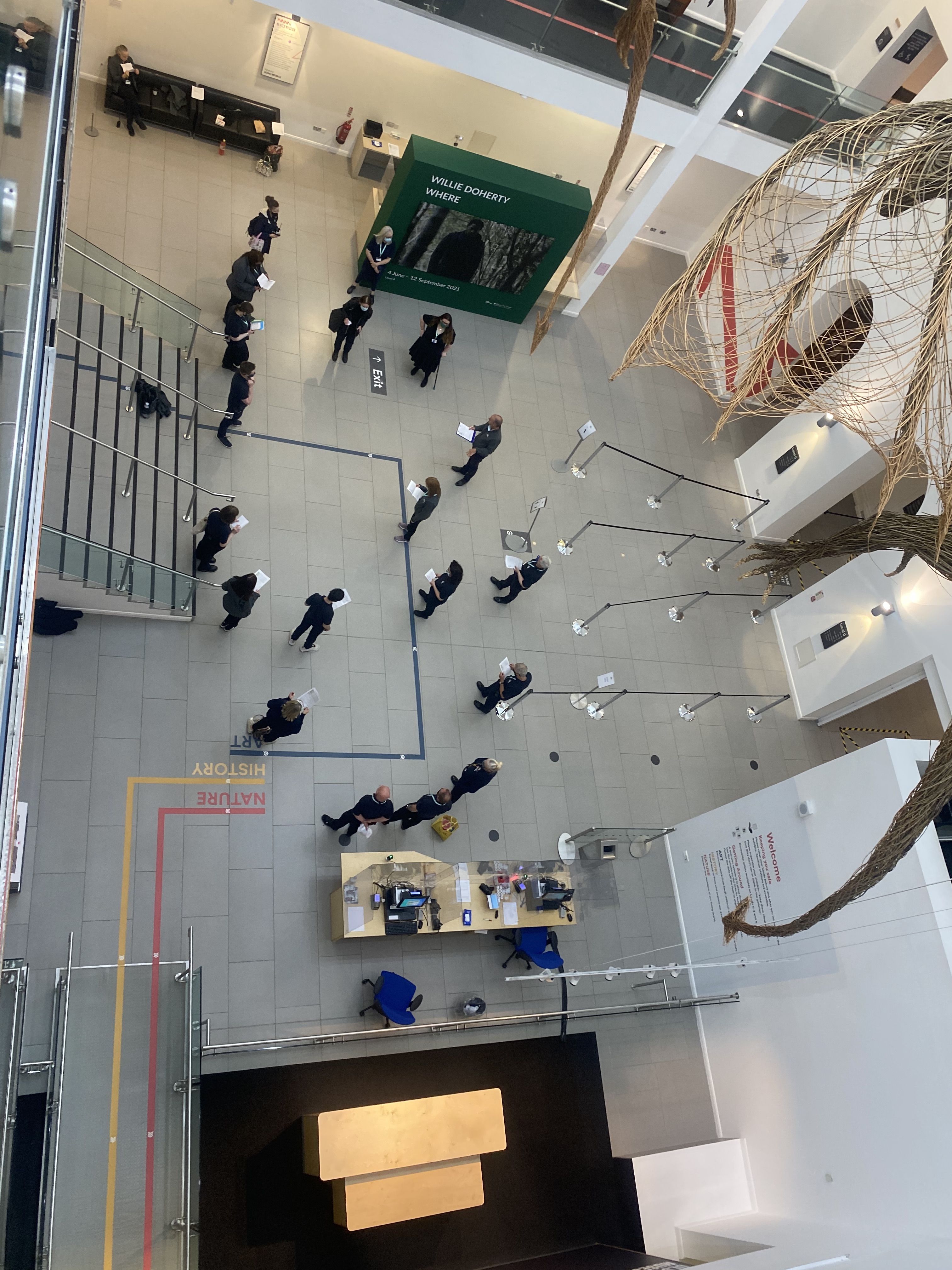

When I was but a nipper, I saddled up with my Ramoan Gardens gang, took my courage in my hands and sallied off across town to visit the Ulster '71 exhibition in Botanic Gardens.

I recall little of that particular odyssey — with the exception of a porter at the entrance counting the numbers attending with a little hand-held clicker. Someone clearly had an eye to the propaganda around a huge attendance boast — even as the city was in flames.

Ulster '71, of course, was a vanity project writ-large for the state of Northern Ireland 50 years after its bloody birth. "Here's us and who's like us?" was the unofficial theme. A sort of "We're not Brazil, we're Northern Ireland" before its time. And what a state their Northern Ireland was in — and it was their show for sure.

That 50-year extravaganza happened just as the wheels were coming off — and the rest is a horror flick that lasted a quarter of a century.

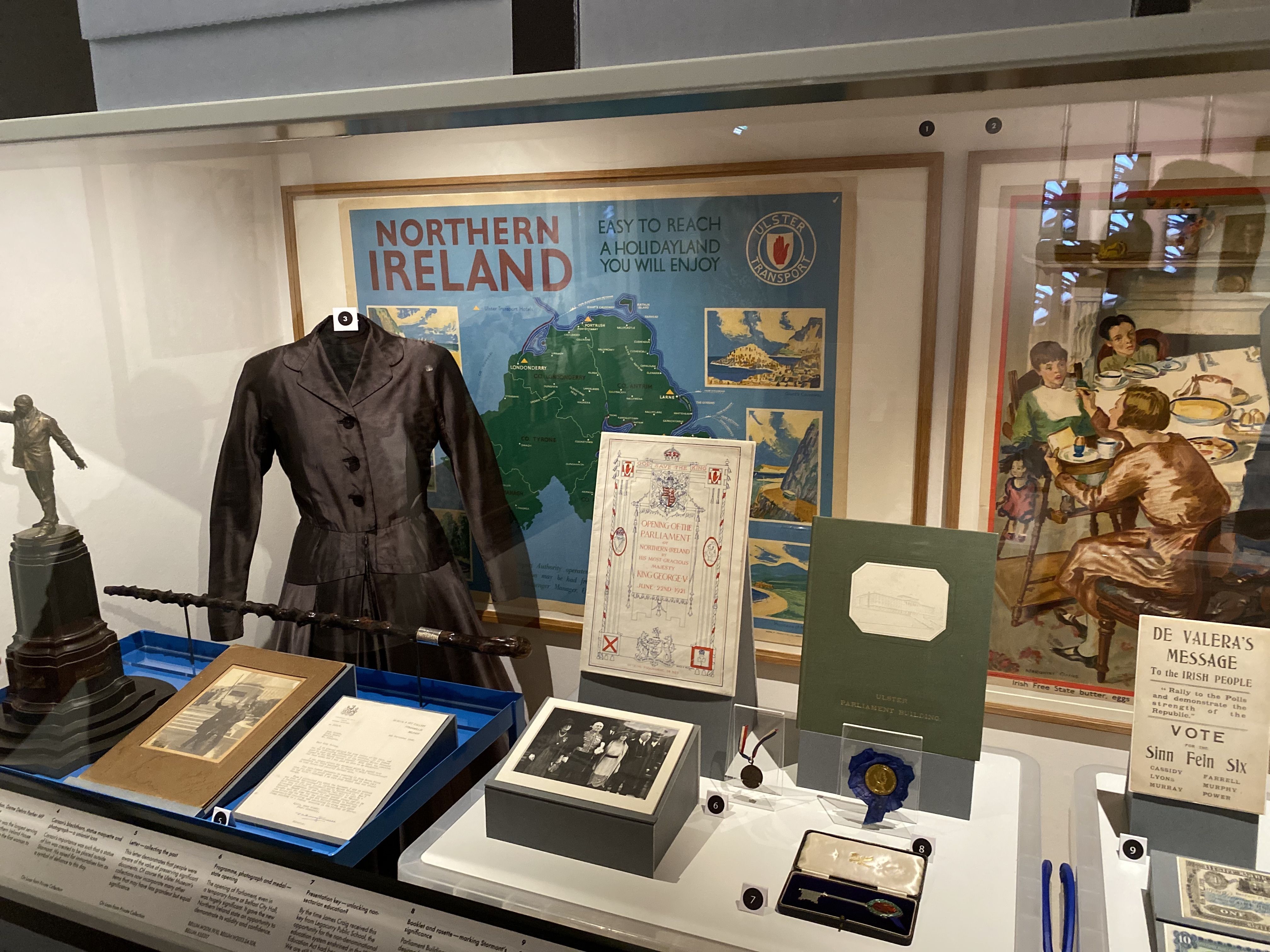

THE PAST IS PROLOGUE: Making The Future display cases at Ulster Museum

The hope was that come the centenary, wiser counsels would prevail and the tub-thumping triumphalism of yesteryear would be consigned to, well, history. Truth be told, Covid probably did a favour for what was left of the dregs of Ulster '71 jingoism by preventing the red-white-and-blue brigade from immersing themselves in sentimental swill.

There is something about that prologue to the exhibition which is like a clearing of the air. A scene-setter which makes it possible to assess and enjoy the carefully-selected artefacts from the Museum's extensive collections across ten decades.

News that the Ulster Museum was presenting its own look back at 100 years of Northern Ireland gave the first opportunity to test if the cognitive dissonance of 1971 had given way to a more sober assessment of all our yesterdays.

ALL ABOARD? Northern Ireland tourism poster and other artefacts.

The ambitious title of the exhibition, 'Making the Future' was an early sign that this would be less a look back in anger than a reflective — even contrite — review. EU Peace Funding and the influence of co-designers the Derry Nerve Centre can be seen in the inclusive approach to the exhibition. But evident also is a desire by National Museums NI (despite its vainglorious title, introduced by a unionist minister) to reflect the desire for a more honest appraisal of how we got here. After all, forget or gloss over our past mistakes and we are surely doomed to repeat them.

UNVARNISHED STATEMENT

Nevertheless, the unvarnished curator's statement on the information board for the exhibition fairly took my breath away: "There is an undeniable sense of exclusion felt by most Catholics and nationalists that was compounded by institutional discrimination and electoral practices designed to maintain unionist political dominance."

It's not the veracity of the observation which stopped me in my tracks — for it is demonstrably true — but the fact that it had been stated at all. Ditto the assertion that "the continued existence of Northern Ireland which for many is a source of pride, is divisive and irrelevant for many others".

TRIBUTE: A Covid quilt from final display case.

There is something about that prologue to the exhibition which is like a clearing of the air. A scene-setter which makes it possible to assess and enjoy the carefully-selected artefacts from the Museum's extensive collections across ten decades.

There is much here to illustrate how two states developed on the island — neighbours forced to orbit, as historian Breandán Mac Suibhne observed recently, different suns. There are shipyard ID cards and ard fheis programmes, glorious portraits of both unionist and nationalist icons by Sir John Lavery, a 1920 poster calling for a boycott of Belfast banks, tourist board brochures for the new Northern Ireland, prison hankies, uniforms, uniforms and more uniforms.

It is all, sadly, behind glass partitions — based on a desire to keep safe objects we would all love to hold rather than a commentary on our division — presented as if the viewer had stumbled into the museum's stores. Though Gloria Hunniford and Máirtín Ó Cadhain sharing the same shelf might be a tad more promiscuous than your average archivist would permit.

PAIRED: A portrait of Gloria Hunniford, poster of Máirtín Ó Cadhain and bust of Joe Tomelty.

The purview over the century just passed concludes, thankfully, on an optimistic note with a jersey for the new East Belfast GAA team and a Covid quilt honouring health workers.

For visitors of a certain age, the eye turns immediately to the depiction of the war years of the seventies, eighties and nineties. The seventies exhibits I found I could handle with equanimity — the scale of the slaughter in the decade of Ulster '71 almost belies any telling. When I rounded the corner to take in the eighties, however, with its decommissioned RPG, British Army flak jacket and H-Block banner, my emotions delivered an unexpected uppercut. I had to turn away and gather myself.

I would be hard-pressed to explain what triggered my upset: Trauma, survivor's guilt, grief, or all of the above? Certainly, the ghost of my grandfather, one of three brothers shot by off-duties in May 1922 in his South Derry home, was at my shoulder throughout my visit. (One brother died, two survived including my granda Tommy. Their attacker was cleared in court and carried shoulder-high down Magherafelt main street.) But my granda was never one given much to emotion, even as he lifted us up onto his knee to touch the shrapnel still lodged his arm.

Had my other dearly departed companions from that awful period risen up unbidden: John Davey, who I last saw in Conway Mill discussing the dire security surrounding his isolated Gulladuff homestead; Bernard O'Hagan, who drove me through the byways and boreens of Swatragh and past the church where he lifted the plate on Sundays; back seat passenger Seán Savage who accepted a lift to the foot of Muckish before setting out on a hike.

TO CHALLENGE AND TO PROVOKE

Or perhaps, we should just put it down to the power of this generous exhibition to elicit emotion, to challenge and to provoke?

Either way, I have no doubt that my contemporaries will gain much from this thoughtful exhibition — even if they bring with them (as they surely should) ghosts of a different political hue.

They say you can't hope for a better past. But you can hope for your past to be told better, for all voices to be heard, for everyone to have a place at history's table.

In that regard, therefore, while just 50 years separate the Ulster '71 PR farce and the peace offering that is 'Collecting The Past/Making The Future', they are, in their approach to our divided past, light-years apart.

And for that, both as outrider in a schoolboy posse then and bus pass holder now, I give thanks.

Due to Covid restrictions, visitors to the Ulster Museum have to book ahead. You can read more about the exhibition in James McCarthy's piece here.