If there's a soundtrack to the tectonic plates of Irish history separating in the bitter Hunger strike year of 1981, it would be Moving Hearts' eponymous album of that momentous year.

And if I was asked to pinpoint the one moment when Ireland's hard past and hopeful future parted company, it was the transformative moment in those unforgettable Moving Hearts concerts when Keith Donald's saxophone rent the air as 'No Time for Love' peaked. Unexpected, out-of-place, shocking — after all this was a Christy Moore Band — that soaring, liberating sound signalled that things would never be the same again (at 21:50 in video below).

What we didn't know was that the source of that explosive call to arms was the grandson of an East Belfast Unionist MP and a skilled musician with over 20 years of live performances under his belt. And neither did we realise (and nor did he) that saxophonist Keith Donald was struggling with that disease which tricks its victim into believing it is a cure for that which ails you: alcoholism.

Moving Hearts being pre-internet, I had lost track of the multi-talented Keith Donald, knowing only that he hailed from Belfast and played a pivotal part in the greatest Irish band of the 20th century.

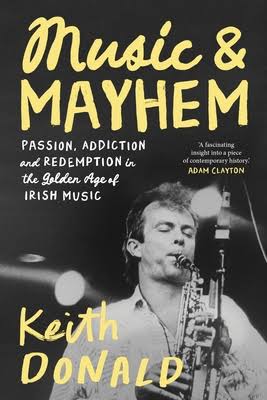

Kudos therefore to 'Music & Mayhem', his autobiography published this year, for reuniting us, fan and hero.

From clarinet protégé making a recording for BBC Ormeau Avenue in 1957 to Irish Arts Council music officer, Donald would have a remarkable story of musical achievement deserving of a literary look back. However, when twinned with his three-decade battle with booze, Donald's memoir becomes a heartbreaking tale of self-destruction on a par with 'A Drinking Life' by that New York writer and son of Belfast Pete Hamill. If that doesn't whet your appetite for this rewarding read, did I mention the author kicks off his opening paragraph with the news that he's being treated for cancer?

Donald sets out his stall early: "This book is about music. Music and drink, not always in that order, and sometimes one about the other. As soon as I found music, or it found me, it took me over. Ditto drink." But this is also a memoir about Belfast, its hard, unforgiving streets of the 1950s and 1960s and its suffocating and unyielding unionist hegemony. And, Jesus wept, it's also about a young, frightened schoolboy being locked in a coal shed by the headmistress for some meaningless indiscretion.

Donald's interest in music, nurtured by his doting grandfather and loving parents, was his lifeline to a future of countless concerts and star-studded reviews. At Methodist College, he perfected his clarinet playing, learning on the side how to down a few scrumpies at lunchtime and return gaily to his lessons in the afternoon. Soon gigging three or four times a week, the young Donald would weigh into school, shattered but walking on air, after snatching a few hours sleep post late-night jazz sessions.

He did have a short outing "as a naive teenager" with an Orange band, answering an ad for clarinet players for a makeshift band on the Twelfth and earning a few bob for his troubles as well as copious libations as the day passed. His verdict, 60-plus years later is unforgiving: 'I would never consider banning the Twelfth but Stormont or Westminster should insist on its triumphalist bigotry being reined in".

As Donald's musical star rose so did his binge-drinking. And while drink was and perhaps still is a mainstay of the Irish entertainment scene, the results were not pretty. There were blackouts, car accidents, arrests and spells in the drunk tank, "crashing through a floor-to-ceiling glass panel", "stories that scare me now". "It was only when I got sober," he writes, "that I came to realise that alcoholism had determined much of the course of my life..I gravitated towards people who accepted the unacceptable. Inevitably they were themselves drinkers with drink problems. We camouflaged each other."

If the author is self-effacing about the many musical milestones which have made him one of Ireland's most revered artistes — writing the scores for films, accompanying Van Morrison on albums, playing at concert halls across Europe — he holds no such inhibitions about revealing the horror of being a full-on drunk.

At 18, our protagonist headed off to Trinity but travelled home often to play with emerging show band outfit the Federals. By 1964, he was recognised as an outstandingly gifted — and prodigiously drinking — musician. From the Federals, he moved up a rung or two to join the Greenbeats in Dublin, gigging four or five times a night across the length and breadth of Ireland while studying for a degree in Latin. By 1969, he was cutting records and earning steady money with showband scene giants The Real McCoy.

"Mostly now I feel lucky: I'm blessed with a wonderful daughter-friend, I'm clean and sober...I have...a lovely Belfast family...and I still love playing music...I feel totally at peace."

It was in that tumultuous year the young Donald made his first clear break with his unionist upbringing - supporting the civil rights movement and speaking up against "the injustices of the North". That led him to a life-time of supporting good causes from the campaign against the Section 31 censorship on RTÉ to the anti-apartheid cause in South Africa.

But neither fame nor social conscience could slow down his drinking. Even as he indulged his first love playing jazz around venues in the capital while completing a masters as UCD, booze was his crutch and companion. His first job as a social worker barely dented his Homeric thirst. Here's an average Friday in 1979: Finish work at 5pm, "few pints" in the musicians' bar then walk to Olympia Theatre to play in the pit orchestra, "a drink or two every time we stop playing", post-show "it's eight or ten pints", two sets at the Trinity Ball, steal half-finished drinks left on tables by students, from 2am wander aimlessly through Dublin backstreets waiting for the early-house to open, 10am leave Slattery's of Capel Street for home and bed. And the weekend has only begun.

Fortunately, for the author and lovers of Irish music there is, rather than the early death which surely was in his stars, redemption and rebirth here. But it's a slow train running. Before he vanquished his demons, Donald teamed up with the newly-formed Moving Hearts crew as they were starting out in early 1981.

Clear winner from me. The mighty Keith Donald’s sax on Before the Deluge (Moving Hearts)

— Pippi (@Pippisell) August 30, 2024

If you don’t listen to the song listen from 4:20 to the end.

I’ve listened hundreds of times and seen him play it live and it stops me in my tracks every time. ❤️https://t.co/Gxjhg5XsN8

A ballsy experiment in Irish music-making, Moving Hearts was unique in many ways. A co-op, it allowed any of its members to veto a song if they didn't approve of its lyrics - a power never exercised in their brief and bright half-life. There was something else which set them apart in the most conservative, church-dominated, censored state in Europe: they wore their progressive politics on their sleeves.

"I'm proud to have been a member of a band that sang about nuclear war, religious hypocrisy, environmental plunder, apartheid, slum landlords and 800 years of colonialism in Ireland," Donald writes. And the punters agreed, sending their debut album, complete with duelling solos of Davy Spillane on uilleann pipes and Donald on saxophone, to the number one spot. He went on to play 110 barnstorming gigs with Moving Hearts in that bleak and bitter year, sending hearts soaring and giving vent to the fury and grief of hundreds of thousands - millions even - whose sorrow was edited out by RTÉ and BBC bosses alike.

Amazingly, even in this very apogee of his career, Donald continued to drink like there was no tomorrow. And did so right until March 1989 when after being stopped by the Guards while driving stocious, he contacted a friend who suggested he call if he ever wanted help to get dry: "a glimmer of hope after twenty-seven years of drinking troubles".

With the support of AA and counselling, and despite some early setbacks, Donald started a second life sober. "What conquers addiction?" he asks. "I think the answer is love, but you have to look for it...Mostly now I feel lucky: I'm blessed with a wonderful daughter-friend, I'm clean and sober...I have...a lovely Belfast family...and I still love playing music...I feel totally at peace."

In another lifetime, a harder time, Moving Hearts, aglow with Keith Donald's sublime saxophone, played the Green Briar, a pub-dance hall on the slopes of Black Mountain above Andersonstown. A security team was designated to look after the rare visiting band in what, for the Andytown audience, was a time of much mayhem and little music. "That night, I felt like the best-protected Prod in Belfast," Donald later joked to this author. I wonder did he know then that from his Green Briar eyrie atop O'Hare's Lane, he could just about see the Tullymore home of fellow-famed saxophonist Des Lee (McAlea) who survived the Miami Showband massacre — and also struggled with the bottle. Or that in the audience, agog, on that hunger strike summer's night, was a fan who would one day review his yet-to-be-written memoir.

Through the awful beauty and numbing pain of 'Music & Mayhem', readers have the chance to relive their own connections, old and new, to the two lives of Keith Donald — his second life only beginning, as the saying has it, when he realised he only had one.

Music & Mayhem, Ketih Donald. Lilliput Press. £17. Keith Donald will be honoured at the Belfast International Homecoming in September. You can read more about his work and his one-man play, which continues to tour Ireland, on his website.