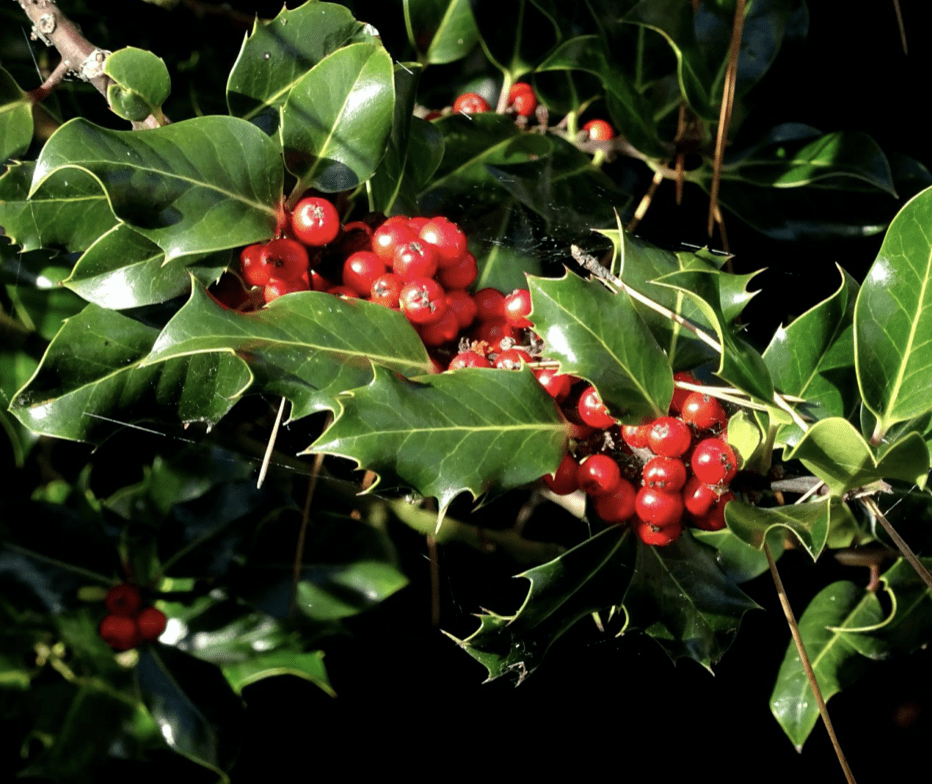

KILWARLIN’S a pretty good spot to get your Christmas holly. More importantly, Kilwarlin’s a pretty good spot for Christmas holly with berries, which is the only kind of Christmas holly really.

Or it used to be a good spot.

I’ve been walking there for a very long time. When my late companion Alfie was a pup my favourite columnist, Dúlra (aka Gearóid Ó Muilleoir), came with me to take Alfie on his first serious walk. We overdid it a bit and the poor thing spent the next two days sleeping. Although I like to think it was that early introduction to long walks that meant Alfie would have dragged you to Dublin and back and wanted out for another walk an hour later.

Kilwarlin is a lovely rural location situated between Lisburn and Moira, and as well as holly with bright red berries, it’s got Kilwarlin Moravian Church where there’s a scale model hewn from earth and water and trees of the Thermopylae battlefield. Check it out online – it’s a great story. The Kilwarlin scale model, I mean, not Thermopylae (although that’s a great story too).

Kilwarlin let me down this year. Completely. On a two-hour walk on a cold and misty Sunday morning with my snippers and bag-for-life at the ready there wasn’t a berry to be seen. I’ve since been told the Cave Hill holly is heavy with berries this year, so I’ll head up there this weekend. But before I do, come with me as we take a walk through the byways and lanes of history, tradition, mythology and botany to find out more about this beautiful and ubiquitous native Irish plant, and why it has come to be so closely associated with the festive season.

What’s in a name?

No. Forget what you’ve been told or what you have held to be the truth all these years. The word ‘holly’ is a not a simple and charming derivation of the word ‘holy’, although the idea is so obvious and attractive that it is to all intents and purposes part of the holly festive narrative. The truth – as it so often is – is altogether more prosaic and practical.

Holly has landed with us after a long journey through the history of Old German (hulst), Old English (holegn), Norse (hulfr) and French (houx). Disappointingly perhaps, each of these ancient words refers in different ways to the qualities of prickliness, spikiness and sharpness for which holly is best-known.

The crucifixion

Many and varied are the reasons that holly is a sine qua non of the Christmas holidays – the first and most obvious being the similarity of the holly’s spiky leaves with Jesus’s crown of thorns. A prickly holly wreath would be reminiscent of thorns on its own, but when you throw in the red berries, redolent of the blood which flowed when the thorns cut His skin, the connection become almost compelling. And the reference to the blood of Christ is the reason why berried holly is the festive favourite.

The holly is also said in some quarters to have been the wood from which Jesus’s cross was made, although – as with the Ark of the Covenant – the truth about the search for the True Cross is likely lost forever in a welter of information, disinformation, claim and counter-claim. Plane, cypress, cedar and pine have also been mentioned down through the years as the wood of the cross, while some Biblical scholars and historians believe the cross was made from an amalgam of different woods – the post and crossbar being made of different woods, the footrest and head sign being made from yet others. But if you thought holly – considered by most to be a bush rather than a tree – is not a carpenter’s wood, then think again. The holly, according to its variants, can be both bush and tree and is, in fact, a very solid and attractive wood which has been used in furniture-making for millennia, particularly as decorative and ornamental inlays and additions. So if the cross was indeed made from a range of different woods, there’s a decent, if not high, possibility holly was used somewhere.

Pagan predecessors

Evergreen plants held a special place in the spiritual lives of Neolithic farmers, Celts, Vikings and Romans. The bright and everlasting leaves were considered almost magical to pre-Christian civilisations. As summer turned to autumn, the harvest was gathered in and the land and its flora began to close down in preparation for winter, evergreen foliage was valued by humans as a sign that life would return in the spring. While the shiny holly and its bright berries offered the promise of continuing life amidst the winter gloom, the sharp and piercing leaves offered a kind of mystical protection to households from the many enemies of naturalistic peoples. The prickly leaves’ protective quality isn’t just mythological – it’s incredibly practical for birds, which find valuable shelter in their pointy embrace.

Since holly was a common and attractive evergreen which had adorned the huts and homes of ancient humans, so, on the arrival and spread of Christianity, it was no surprise that holly was quickly and efficiently retasked to suit the purposes of the Christian narrative.

Berry interesting…

TRADITIONAL: The robin is often seen on holly in real life as well as on Christmas cards as it loves the red berries

Since it’s probably only a matter of minutes since you learned that holly isn’t another word for holy, I hesitate to overburden you with more well-I-never! information. But here goes: The famous holly berries aren’t berries at all.

Nobody’s going to fight with you if you go on calling them berries, as I will, but technically they belong to a genus of fruit known as drupes. Since you may be reading this listening to carols in an easy chair by the Christmas tree with a glass of Bailey’s in hand, I’m not going to interrupt your contentment with dry science, so let’s make this simple…

Every berry has a casing that is designed to fail. When the time comes for the seeds or pips inside to be released, part of the berry’s skin ruptures, allowing the seeds to be released and reproduce.

The casing of the drupe, on the other hand, is more robust and not designed to fail. The seed inside is released in two ways: by natural degradation of the outer shell in the soil where it falls; or via the stools of predators which digest the casing and fleshy pulp, but pass the stones or seeds. In Ireland, these predators are overwhelmingly birds in the case of holly berries (sorry, drupes), but can also be squirrels and deer. And yes, since you're asking, robins absolutely love holly berries.

Other well-known drupes are olives, apricots, plums and cherries.

But since we’re all happy calling them berries, and since the word ‘drupe’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘merry’, let’s for Santa’s sake pretend the last five paragraphs never happened.

Mary’s Boy Child (or is it Girl?)

On that earlier holly hunt I told you about, I wasn’t simply looking for holly with berries (look, I told you to forget about the drupes thing) – I was looking for female holly. Because it’s only the female holly shrub or tree that produces berries. I can see you’re still in that comfy chair with your Baileys, so let’s again keep this simple.

Holly is dioecious, which means it requires a male and female to reproduce. This differentiates it from most other shrubs and trees which are either monoecious or cosexual – meaning they reproduce on their own.

Reproduction takes place via of insects, which transfer pollen to the holly flowers in the spring. Before the late-autumn appearance of the holly berries, you can tell the male from female by their flowers. They both produce four-petalled blooms in the summer, but the male and female flowers are distinguishable by the shape of the reproductive stamen at their centre. Which begs the question: Why would you want to when you can wait to autumn when it’s ten times easier at Christmas?

Oh, and remember – if you forget your chain-mail gloves when you go holly-hunting this year, bear in mind that not every holly leaf is a prickly danger. The further up the shrub or tree you go, the less spiky the leaves, until at the very top you'll find that the leaves are flat and harmless. Which is good news only if you've forgotten your gloves but remembered your ladder.

Now there's an idea for a good Christmas present.