Conor McParland and Robin Livingstone are two Andersonstown News journalists at opposite ends of their careers. Together they visited the new St Comgall's conflict exhibition to find out how the past speaks to those who lived it – and those who are learning it...

Conor McParland

HAVING been born in 1991, I was brought up on first-hand accounts of people who lived through the dark days of the Troubles. From my mum, a child growing up in Andersonstown, to my granny, who hailed from the Lower Falls, I was able to get a sense of what life was like.

My experience as a journalist for the last 12 years with the Andersonstown News has enhanced my knowledge further, in particular interviewing and listening to people who lost loved ones during that time.

The new ‘The Falls – Where The Troubles Began’ visitor exhibition at St Comgall's has been on my to-do list since it opened last autumn and finally last Friday morning, I got the chance to see it for myself. In the company my colleague Robin Livingstone, who lived through the days of which the exhibition speaks, and whose words are part of the interactive narrative.

The exhibition tells the story of the outbreak of conflict on the streets surrounding St Comgalls in 1964 and then again in 1969 and 1970. It is not the story of the Troubles as a whole, but it is a very detailed story of what happened in a small and particular area of West Belfast.

We were welcomed to St Comgall's by Gerry McConville and Marie Maguire from Falls Community Council before their colleague Seán Mag Uidhir provided me with headphones, an audio guide and a brief explanation of how the exhibition works.

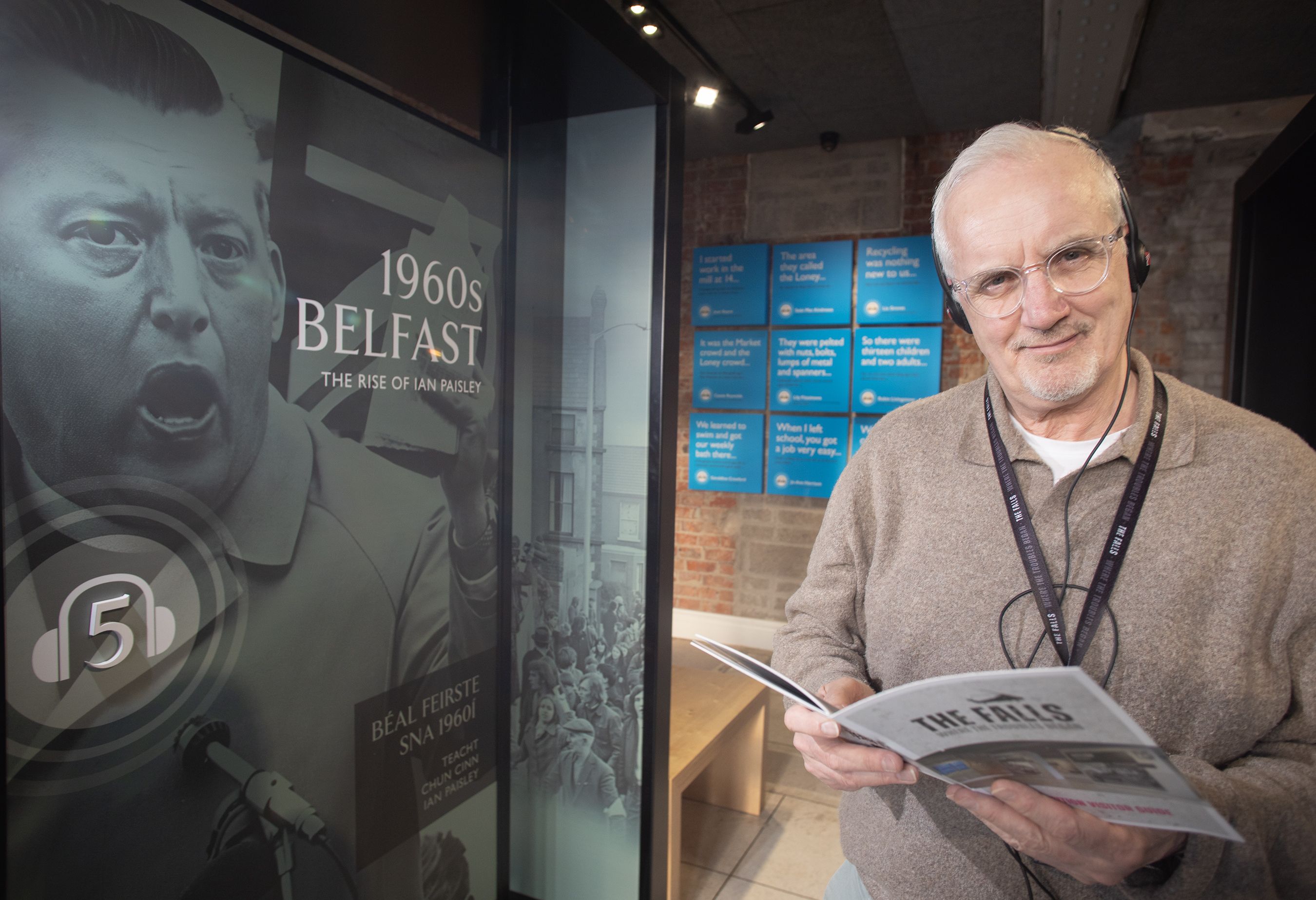

Conor McParland and Robin Livingstone

It starts off setting the scene for the conflict that was about to happen when a nationalist minority was dominated by a unionist-controlled state. Catholics were treated differently when it came to houses, education and jobs. In the 1960s, a civil rights movement demanded reforms which were strongly opposed by the unionist government.

The next stage is a 15-minute film which brings together archive footage of some of the key milestones in the early years of the conflict. It begins in 1964, when the removal of the Irish flag from the election headquarters of Sinn Féin directly opposite St Comgall's sparked the Divis Street Riots. I then learnt about the civil rights movement of the late 1960s and the mobilisation of Ulster unionism against the proposed reforms.

The third part of the exhibition focuses on the 1969 chaos on the Falls when loyalists poured down the streets connecting the Shankill with Divis and the Falls where many Catholic homes were targeted and burnt.

The fourth part focuses on the Falls Curfew, when in July 1970 the British army swamped the Falls in search of IRA weapons. Protests and resistance led to further violence, including the death of three local people and a visiting photographer. I was taken back by what happened next – the Curfew was broken by local women who marched from Andersonstown down the Falls Road. It was a remarkable act of solidarity, as was the re-building of Bombay Street by local people.

The exhibition concludes with a roadmap to peace. Key figures include Gerry Adams and local Redemptorist priest Fr Alex Reid. It was a slow process but one that laid the foundations of the Good Friday Agreement and the peace we enjoy today.

What really made the exhibition for me are the blue wall-mounted panels that appear throughout, featuring vivid and intimate memories and recollections of people who lived through those years. Curated by Falls Community Council through the Dúchas Oral History Archive Project, they bring an authentic and lived dimension to the historical storytelling.

The detail is remarkable and I doubt if anything has been missed. It is remarkable to me that so much happened across such a relatively small part of West Belfast. I was moved, especially by the eyewitness accounts of how hard those days were, but, equally, I was inspired by the community spirit that there clearly was in abundance.

‘The Falls – Where The Troubles Began’ is quite simply a must-see.

Robin Livingstone

THERE'S not much in the St Comgall's exhibition with which I'm not familiar. How could I not be? I went to school there during the period in question and lived a hundred metres away across Divis Street in a handsome three-storey home in Dover Street out of which we were burned in August 1969.

But seeing the epochal events of the mid- and late-60s laid out before me in such a fascinating and accessible way had the effect of turning me into a wide-eyed tourist. What I was seeing and listening to was literally This Boy's Life, but to have it rendered to me in such immersive, not to say cinematic, drama meant that it felt like a piece of history, a piece of storytelling, I was hearing and seeing for the first time. For this is not just an exhibition for visitors to our city or to our island, it is as compelling and fascinating to Belfast people like me who thought – and think – that they know it all.

I visited the exhibition in the company of my colleague, East Belfast man Conor McParland, who was born three short years before the first ceasefire. He's a journalist working in Belfast so of course he's familiar with the broad outline of what happened when the balloon went up in 1969. But to explore the sometimes poignant, sometimes brutal intimacies and intricacies of my boyhood streets with him, to see and hear his shock and surprise, his empathy and his outrage, was a turbo-charge to my memory.

Robin Livingstone

I well remember St Comgall's when it was my primary school – the classrooms laid out in a circle around a central courtyard on whose well-tended grass we could not set foot. We moved from place to place along corridors that in truth were more like cloisters and the memories of 1969 linger there today with the semi-sacred, whispered urgency of an ancient monastery whose stillness is only amplified by the headphone roar of a crowd or the whoosh of a flame tearing through a burning home. That's due in no small part to the incredibly sympathetic way in which the exhibition designers have brought together the building's architectural past and the very considerable modern demands of an infotainment experience.

My St Comgall's remains: the bullet-scarred old building is still filled for me with the smell of school dinners and the playground shrieks of two hundred boys. But there's a new St Comgall's too – one waiting to share the history and the secrets of the district it served with those hearing them for the first time. Or indeed with Belfast people like me who also want to hear those stories for the first time. Again.

The exhibition draws on two important post-conflict community archives: the Dúchas Oral History Archive and the Belfast Archive Project. It has been made possible with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, thanks to National Lottery players.